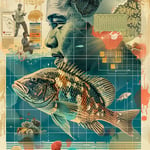

The spread of blackchin tilapia across numerous provinces seems to be a consequence of smuggling, while measures like electrofishing, coupled with the introduction of other predatory species, might offer a viable solution to control their burgeoning population, as per academic experts.

Recently, Chulalongkorn University’s Communication Center and Aquatic Resources Research Institute (ARRI) hosted its 24th “Impact” academic seminar, spotlighting the relentless proliferation of the blackchin tilapia.

The seminar attracted academics from various universities, institutes, and agencies, all eager to share their perspectives.

Prof Wilert Puriwat, the acting president of Chulalongkorn University, commenced the event with an opening speech, underscoring how the spread of this Western African fish species is disrupting multiple sectors.

“This year’s seminar is pivotal. It aims to foster cooperation among experts across diverse fields to tackle this pressing issue, with the findings set to be handed over to governmental bodies for action,” he asserted.

Prof Suchana Chavanich, the ARRI vice director, shed light on the historical context, stating, “The blackchin tilapia was introduced into Thailand long ago for commercial purposes. Unfortunately, importers often overlooked the detrimental impact this species has on local ecosystems and other aquatic species.”

She voiced the urgent need for Thailand to pay heed to the situation and implement regulations targeting both legal and illegal imports of foreign species, emphasizing a proactive rather than reactive approach.

Addressing the query of whether the blackchin tilapia proliferating in 17 provinces hail from a single source, Asst Prof Wansuk Senanan, an aquatic science lecturer at Burapha University, believed otherwise. She referenced reports by the Department of Fisheries from 2018 to 2020, which noted initial waves of invasion in Samut Songkhram, Samut Sakhon, Phetchaburi, Prachuap Khiri Khan, Samut Prakan, Chumphon, and Rayong, suggesting these occurrences weren’t isolated incidents.

“The significant lessons we’ve derived from the blackchin tilapia invasion and the resulting ecological harm highlight the necessity for robust risk assessments and well-thought-out response strategies,” she elaborated.

Providing a practical solution, Assoc Prof Dusit Suksawat from the electrical engineering department at King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang (KMITL), advocated for electrofishing. “This method is highly effective in controlling fish populations and has the added advantage of being environmentally friendly,” he explained.

On a genetic front, Kasetsart University’s genetics lecturer Assoc Prof Anongpat Suttangkaku proposed genome editing of the blackchin tilapia as another feasible strategy.

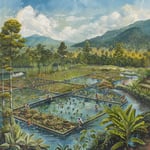

Elaborating on the current biological control approaches, Department of Fisheries’ official Kongphop Ampolsak pointed out that the agency is deploying two main methods. Firstly, the release of predatory fish species like the Asian seabass and long-whistled catfish to curtail the tilapia numbers, and secondly, the introduction of genetically modified sterile blackchin tilapia, which have been engineered to possess four copies of each homologous chromosome (4n).

In summary, while the blackchin tilapia problem is multifaceted, the combined insights from academia, robust risk assessments, and innovative control techniques hold promise in mitigating this ecological challenge.

The idea of electrofishing seems quite effective and environmentally friendly. Maybe this should be the main solution going forward.

Sure, it sounds good on paper, but what about the unintended consequences? Electrofishing can harm non-target species too.

That’s a fair point, but isn’t it a lesser evil compared to letting an invasive species wreak havoc? We should at least consider it.

But how practical is it to use electrofishing on such a large scale? It’s not like we can cover every water body effectively.

I think introducing predator species like Asian seabass could lead to its own set of problems. Look at history, whenever humans try to meddle, things go wrong.

Historically, you’re right, Sara. But if done properly, with thorough risk assessments, it could be a game-changer. This isn’t a new idea without merit.

What if these predator species start competing with local ones? Could this create a double-edged sword situation?

Interesting take on genome editing. It’s high time we use advanced biotechnology to solve ecological problems.

But isn’t tinkering with genomes risky? What if the edited species mutate in unforeseen ways?

Every technology carries risks, but isn’t it worth trying given the severity of the tilapia problem? We can always place checks and balances.

Are you willing to experiment with nature at such a high level? We can’t even control GMO crops properly, let alone live animals.

I’m concerned about the smuggling issues. How can we stop illegal imports effectively?

Strict regulations and harsher penalties might deter smugglers. Unfortunately, enforcement is always the weak link.

What if local authorities are part of the problem? Corruption can undermine any regulation.

Government intervention is key here. They need to take coordinated action based on the experts’ recommendations.

Government intervention always sounds good until it becomes bureaucratic red tape. Action needs to be swift.

True, but without government backing, any solution will be half-baked. We need policy changes and fast implementation.

Sad to see how commercial interests always outweigh environmental concerns. This mess could have been avoided.

While that’s true, we must focus on solutions now. Blame won’t resolve the issue at hand.

Sure, but acknowledging the root cause helps prevent future mistakes. Both need to happen concurrently.

The historical context is crucial. Learning from past errors is the best way to move forward efficiently.

I think the introduction of genetically modified sterile blackchin tilapia is fascinating. It could be the least harmful approach.

Isn’t it ironic that we ourselves caused this problem through negligence and are now scrambling for solutions?

The academic community is doing its part. Let’s hope policymakers heed their advice and act accordingly.

Indeed, translating research into policy is the biggest hurdle yet.

Why not integrate a combination of all these strategies? Different areas might benefit from different approaches.

Couldn’t local communities get more actively involved in these mitigation efforts? They are directly impacted.

Great point, Lara. Community engagement could actually be the missing link. It can foster better adherence to the proposed strategies.

It’s all about finding a balance. Total eradication of invasive species might not be possible, but control is.

Eduation campaigns can help too. Informing the public about these issues can change behaviors and reduce illegal activities.

Absolutely, Kriti! Empowering people with knowledge can lead to grassroots movements that make a tangible difference.