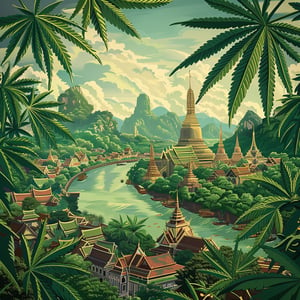

In the verdant, sprawling expanse of Khao Yai National Park, a drama unfolds that could rival the plot twists of a classic novel. At the heart of this captivating storyline is National Parks Chief, Chaiwat Limlikhit-aksorn, a man who stands unwavering in his belief that a contested piece of land rightfully belongs to the park’s lush realms. This is no ordinary land dispute; it’s a clash of titans, with the Agricultural Land Reform Office (Alro) challenging his assertions, ready to ignite the legal battlefield.

Picture this: two factions, each armed with their evidence, like duelists at dawn, waiting for the signal to present their cases. Chaiwat, with the calm of a seasoned warrior, suggests that the tiebreaker lies with the One Map Preparation Committee, a group of wise sages appointed by the grand National Land Reform Committee. “Let them decide,” he declares, poised between the thresholds of a lawsuit and vindication. His confidence is palpable – if the land is ruled to belong to Alro, he’s ready to face the music. But should the scales of justice tilt in favor of Khao Yai National Park? Well, he’s got a counter lawsuit up his sleeve. “We have ample proof,” Chaiwat asserts, the twinkle in his eye reminiscent of a protagonist who knows the climax of the story yet remains tight-lipped.

Enter Alro, escalating the narrative tension, not by a notch but by leaps and bounds. They accuse Chaiwat of a clandestine operation on a fateful February day – the removal of 27 demarcation markers, concrete sentinels meant to define the boundaries of agricultural land. But our protagonist is unshaken, steadfast in his conviction that these markers trespassed into the territory of Khao Yai National Park.

Amidst this legal tussle stands the Alro secretary-general, Vinaroj Sapsongsuk, a man who, just the day prior, described how Amarit Khongkaew, acting like the carrier pigeon of justice, flew to Mu Si police station in the quaint district of Pak Chong to file a police complaint against Chaiwat. The stage is thus set for a showdown that promises to be both enthralling and heart-wrenching.

The contentious piece of land, all 72 sections totaling almost 3,000 rai, finds itself at the center of a tug-of-war. Alro claims this land, part of a vast 33,896 rai, was bestowed upon the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives in 1987, earmarked for an agricultural reform scheme designed to uplift landless farmers. Yet, the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP) – Chaiwat’s bastion – argues that the entire expanse is ensconced within park boundaries established in 1962.

In a tale that weaves together the threads of environmental stewardship, legal drama, and human ambition, the dispute over Khao Yai’s land is more than just a conflict; it’s a narrative ripe with lessons on coexistence, governance, and the preservation of our planet’s natural treasures. As this saga unfolds, one can’t help but be drawn into its intricate plot, eager to see how nature’s guardians navigate the complex labyrinth of laws, evidence, and counterclaims. Khao Yai National Park and its surrounding controversy serve not merely as a battleground but as a testament to the enduring spirit of those who strive to protect Earth’s majestic landscapes.

It’s clear as day that Chaiwat and his team are the heroes here. Preserving natural parks should be our top priority. Land reform’s important but not at the expense of losing our precious natural reserves.

Easy for you to say from the comfort of your city apartment. People need land to live and work. Not everyone has the luxury to prioritize conservation over livelihood.

But if we don’t preserve these lands now, there won’t be any land left to live on. Think long term, please.

I understand the need for land, but must it come at the cost of our natural heritage? There has to be a better solution that benefits everyone.

This case is fascinating from a legal standpoint. It’s not just about the land—it’s about how we interpret and enforce laws dating back decades. Can’t wait to see how this plays out in court.

Agree. But it’s disappointing how these legal battles drag on for years, draining resources that could be used more productively elsewhere.

We’re missing the bigger picture here. It’s not just about this one piece of land. It’s about how we’re dealing with the crisis of climate change and the rapid loss of biodiversity. These natural parks are vital.

Vital, yes, but so is feeding our people. Climate change is important, but so is the immediate need of the population. There’s got to be a balance.

The irony is, much of the land used for what we call ‘conservation’ was once cultivated and lived on by indigenous peoples. We’ve displaced them in the name of ‘conservation’. Something about that doesn’t sit right with me.

Exactly, our voices are often ignored in these discussions. Our ways of life have been sustainable and in harmony with nature long before these laws were in place.

As someone living close to Khao Yai, this whole saga affects us the most. We’re caught in the middle, watching these power plays, hoping for a resolution that benefits our community too.

It’s important to hear the perspectives of locals like you. Often, the discussion becomes too polarized with people not directly affected by the outcome.

Chaiwat’s stance signifies a bold step towards the preservation of our natural heritage. However, it might be also seen as an impediment to the progress and development that can uplift many lives. A true moral dilemma.

This clash between conservation and agriculture reform is a classic example of the trade-offs society must face. The key is finding a sustainable balance that can serve both our ecological and economic needs.

Khao Yai is a gem that needs protecting, no doubt. But let’s also not forget the rights and needs of the people. Perhaps more community involvement in decisions would lead to better outcomes for all.