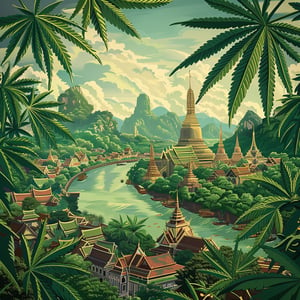

In a world where history is often found more in glass cases and grand halls than its original hearths, the tale of the “Golden Boy,” a magnificent statue of the Hindu deity Shiva, and a mysterious kneeling female figure, arms raised in eternal supplication, stands out as a saga of return and redemption. The players in this narrative are none other than the esteemed Fine Arts Department and the venerable Metropolitan Museum of Art, embarking on a journey to return these treasures to their ancestral home.

The intricacies of this tale unfurl with the Fine Arts Department at the helm, having been charged with the noble task of collaboration with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Their mission? The repatriation of the two enigmatic artifacts back to the land of smiles, Thailand. This intricate ballet of diplomacy will pirouette through the Royal Thai Consulate-General in New York, with the museum graciously bearing the gilded expenses of this repatriation initiative.

Imagine the air filled with anticipation as repatriation ceremonies are poised to unfold across two worlds – in the venerable museums of the United States and the heart of Thailand, the Bangkok National Museum. This May, an air of celebration will envelop the Bangkok National Museum as it becomes the stage for these prodigal artifacts to make their grand re-entry, with plans to showcase them in all their historical and cultural glory following their arrival.

Sermsak, a name now synonymous with this grand venture, revealed that the Metropolitan Museum of Art is meticulously piecing together the repatriation puzzle, ensuring every detail is perfected for Thailand’s contemplation. Further magnifying the scope of their ambitions, Thailand is simultaneously weaving efforts with U.S. agencies to bring home artifacts from the ancient town of Si Thep in Phetchabun province, painting a vivid picture of cultural restoration.

Last year, whispers turned into headlines when Reuters brought to light the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s commitment to healing historical wounds. The museum vowed to return over a dozen pieces of ancient artwork to Cambodia and Thailand, a decree spurred by their association with the art dealer Douglas Latchford. Latchford, a figure shrouded in controversy, was indicted for allegedly orchestrating a complex scheme to distribute looted Cambodian antiquities across the global art market. Despite his denials and subsequent passing in the following year, his legacy remains intertwined with the saga of these artifacts.

This chapter in the repatriation narrative sees the museum extending its hand to return 14 Khmer sculptures to Cambodia and a pair to Thailand, etching a commitment in stone. This ongoing endeavor to repatriate artifacts is a testament to a shared conviction in the importance of reuniting cultural heritage with its rightful origins, a quest that transcends borders to restore fragments of history back into the fabric of their birthplaces.

Indeed, as these lost treasures make their voyage home, escorted by the guardians of history and culture, they do not merely return as inanimate objects. They return as emissaries of a past that continues to live, breathe, and inspire, bridging the chasm between the past and the present. In their silent beauty, they whisper tales of civilizations long gone but never forgotten, now finally returning to the embrace of their homeland.

This is a monumental step towards righting the wrongs of the past. Artifacts like the Golden Boy and others are not just pieces of art; they are fragments of history and identity. Returning them to their countries of origin restores a part of that identity that was taken.

Absolutely! It’s heartwarming to see these pieces finally going back to where they belong. It’s not just about the physical return, but the acknowledgment of past mistakes and an effort to make amends.

While it’s great to see these artifacts returned, let’s not pat ourselves on the back too hard. The art world is still full of looted pieces. This is just the tip of the iceberg.

But does returning these artifacts really change anything? Or is it just a feel-good measure? The damage has been done, and cultures have been irrevocably changed.

It’s true that this doesn’t undo the past, but it’s an important step in acknowledging and repairing it. Artifacts hold cultural significance and their return is symbolic of respect and understanding.

It’s a complex issue. Museums worldwide house countless pieces whose provenance is murky at best. Repatriation is noble, but it also raises questions about the universality of art and the role of museums.

True, the universal access to art is important. But shouldn’t we prioritize ethical considerations? We can’t ignore the colonial contexts in which many of these artifacts were acquired.

Exactly. Accessibility and appreciation of art on a global scale is crucial, but not at the expense of ethical provenance. It’s a fine balance, but morality should lead.

While the return of these artifacts is commendable, it is essential to not forget about the importance of preserving global heritage. Are we risking making culture too insular by insisting on repatriation?

That’s a valid concern, but repatriating artifacts doesn’t make culture insular. Instead, it shows respect for the origins of these items. It’s about honoring the context from which they come.

Fair point. Respect for origins is crucial. Still, it’s important for there to be a global platform where the world’s cultural heritage can be appreciated by all.

This is more than just returning a piece of art; it’s about returning dignity and a piece of history to its rightful owners. Every artifact has a story and a context that can be fully appreciated only in its homeland.

Here’s an idea: why not create digital replicas of these artifacts? That way, they can be returned to their original countries and still be accessible worldwide.

Digital replicas are a great tool for accessibility, but they can never replace the experience and aura of seeing the original piece. Still, it’s a step in the right direction for global education.