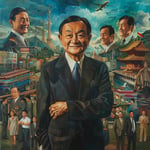

In the heart of Narathiwat, where the vibrant culture fuses with buzzing local life, Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra, often enveloped by a throng of eager citizens, stands as a beacon of hope and resilience. On a particularly brisk January afternoon, armed with unwavering resolve, she met with locals, discussing the ever-mounting wave of household debt—a burden that looms ominously over countless families. As flashes from camera bulbs punctuated her visit, she spoke candidly about a novel idea that her father, the illustrious former prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra, had floated—a potential silver bullet for the nation’s financial struggles.

With a voice tinged with a plea for understanding, Prime Minister Paetongtarn addressed the buzz circling her father’s debt solution suggestion, urging the people not to politicize what she insists is simply a well-intentioned plan. The proposal, though stirring up political tempest, is rooted in a desire to disentangle household finances. “Don’t trivialize this into a political squabble,” she implored, as tensions in the government corridors began to thicken in anticipation of the upcoming censure motion.

The plan—simple yet profound in its potential impact—involved allowing private companies to buy and manage debts from banks. The approach, as articulated by former Prime Minister Thaksin while campaigning in Phitsanulok province, aims to declutter the suffocating financial obligations resting heavily on families’ shoulders. By facilitating a gradual repayment scheme with new creditors, this idea seeks to offer families not just clemency but a fighting chance at a renewed start, free from the haunting shadow of credit bureau blacklists. Absent of government funding, the solution pivots on private companies uplifting financial burdens.

Finance Minister Pichai Chunhavajira weighed in, acknowledging the merits of debt restructuring—an alternative remedy akin to nurturing a fledgling sapling into robust prosperity. He hinted at adopting a “good bank-bad bank” model, reminiscent of strategies that tamed the financial chaos post-1997 crisis. By separating the unruly debt from the healthier loans, banks might find solace, although this calls for cooperation and perhaps the allure of private interest, facilitated by government intervention poised to pave pathways.

“But this government initiative remains in infancy—a seed that requires careful cultivation,” Mr. Pichai remarked, gesturing towards the doors of Thai Bankers’ Association where much-needed discourse is awaited. The myriad of voices fueled debates, notably from Thirachai Phuvanatnaranubala, a former finance minister, who challenged the proposal for overlooking the roots of financial woes. His social media musings—read by thousands—questioned if merely shuffling debt from one entity to another truly extinguishes the economic inferno.

The staggering figures: 16.3 trillion baht in household debt as chronicled by Kasikorn Research Centre, threaded a bitter reality. Amid such fiscal despair, one could argue that innovative, albeit ambitious measures, merit exploration. Yet, as some skeptics point out, the intricacies of these plans—requiring companies wielding immense financial might (about 500 billion baht each)—highlight formidable challenges. The arithmetic is daunting, pondering whether 32 companies could rise to the occasion, shouldering the nation’s debt-laden mantel.

Prime Minister Paetongtarn’s journey to address household debt is one woven with both visionary optimism and pragmatic caution. As she stood amidst the Narathiwat locals, with whispers of hope and determination swirling in the warm air, one could sense her commitment. The path ahead is congested with hurdles, both legislative and economic, but buoyed by a robust debate and the burning will of the people, possibilities linger. Whether Thaksin’s proposal finds its footing or falls to skepticism, one thing remains clear: the quest to alleviate household debt is a clarion call resonating through Thailand’s choreographed dance of tradition and progress.

This new debt solution sounds like a political move more than a practical one. Isn’t it just shifting debt around rather than solving the root cause?

Perhaps, but every new policy needs time. Debt is complex, and untangling it requires innovative approaches like this one.

I get that, Sophia, but without addressing why people got into debt, aren’t we just delaying another debt crisis?

Managing debts through companies instead of government seems risky. What if these companies prioritize profit over helping people?

I think Thaksin’s plan could be a game-changer! Big financial issues need big solutions, even if they’re controversial.

True, Rina. But I’m worried about how feasible it is. Can we really expect enough companies to take on such a massive responsibility?

It does hinge on a lot of trust in the private sector, Natthapong. Maybe incentives could make it attractive for them.

If executed well, this could help families breathe easy. But what assurances do citizens have about these new creditors being fair?

Why is nobody talking about the ‘bad bank’ concept? It sounds like a temporary fix rather than a permanent solution.

Because, Ploy, the ‘bad bank’ idea has worked before and could potentially stabilize things temporarily. Isn’t that better than nothing?

Stability is important, Rajat, sure. But what’s next? We need long-term solutions, not just temporary patches.

Honestly, I sympathize with Paetongtarn’s plea to not politicize the debt solution. Too often, politics clouds initiatives aimed at genuine help.

I wonder if splitting the debt is enough. Shouldn’t there be more education about financial literacy alongside this plan?

You’re spot on, Maya. Education could help prevent future issues. Solutions should empower people, not just fix problems.

Absolutely, Derek. Financial empowerment starts with the basics, right? Classic case of prevention being better than the cure.

The skepticism around this plan is valid, but doing nothing isn’t an option. Let’s see if it breeds success or lessons learned.

I’m worried about how this affects international confidence in our economy. Can foreign investors trust Thailand’s financial decisions?

Indeed a concern, Ling. But if successful, it might enhance credibility showing innovative financial problem-solving.

What role does the Thai Bankers’ Association play here? Seems like more stakeholders should publicly voice their stance.

You’re right, Zara. Stakeholder transparency can ease public anxiety. This type of collaboration needs open communication.

Remember post-1997 strategies? They worked then, so replicating that success isn’t far fetched. It requires cooperation though.

Thaksin’s influence never seems to fade. It’s like a legacy move from him. Curious to see if it really revolutionizes household finances.

If we fill in the gaps on why families fall into debt first, maybe we won’t need these massive reform policies later.