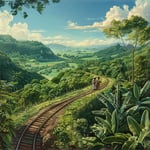

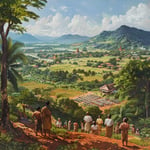

Amidst the captivating landscapes of Buri Ram, specifically from the pinnacle of Khao Kradong Forest Park, an escalating land ownership drama is unfolding. This picturesque province, while usually known for its natural beauty, has transformed into a heated battleground over a 5,000-rai expanse whose ownership is contested between the State Railway of Thailand (SRT) and more than 400 local villagers. With high stakes and influential figures involved, the story unfolds much like a gripping legal thriller.

On the one hand, we have Deputy Prime Minister Suriya Jungrungreangkit, who stands firm like a fortress, asserting that this swath of land rightfully belongs to SRT. According to him, legal mandates are crystal clear—the SRT must claim what is theirs following a decisive verdict from the Supreme Court. Failure to do so could potentially summon a cavalcade of legal repercussions, tarnishing the integrity of one of Thailand’s pivotal state enterprises.

In stark contrast, Deputy PM Anutin Charnvirakul plays a more mediative role in this saga, extending his olive branch by appealing to all parties for patience—a rare commodity in such high-stake disputes. His proposal is to await a ruling from the Supreme Administrative Court, a proposition that sounds reasonable amidst the cacophony of claims and counterclaims. With bated breath, parties embroiled in this land spat await the hammer of justice to hit its final gavel.

Yet, in this labyrinth of legalities, complexity reigns supreme. Enter Deputy Interior Minister Songsak Thongsri, who adds a twist to the tale by suggesting the possibility of an error on the SRT’s part. He champions the villagers’ cause, arguing that their land title deeds are legitimate, touching a chord with those who believe land ownership should honor history and heritage as much as statutes and scribbles on official papers.

The complexity doesn’t end there. This land dispute also encompasses twelve local state agencies, whose structures stand firmly atop the contested land like watchful sentinels. Deputy Prime Minister Suriya proposes compensation, a diplomatic move that seems to echo ‘make love, not war’ sentiments. Yet, should peace prevail, some agencies might even get a gracious permission to lease the land, echoing successful precedents such as the Criminal Court’s leasing of SRT’s land on Ratchadaphisek Road.

As tensions simmer, Mr. Anutin remains steadfast in his commitment to justice, instructing the Department of Lands (DoL) to adhere strictly to the law. The DoL, locked in an intricate dance of legal responsibilities, has found itself now tasked with nullifying title deeds, echoing a directive from the Central Administrative Court’s earlier ruling. But can justice mollify the concerns of land owners and state enterprises alike? Only the forthcoming judicial decision will reveal the fate of this serene yet contested land of Khao Kradong.

In this epic tale of land, law, and livelihoods, the players are drawn into a saga that is etched deeply into the soil of Buri Ram. The winding corridors of justice might eventually find a winner, but as this tale unfolds, one thing remains—hieroglyphic-like maps and historic deeds paint a picture where justice, fairness, and resolution strive to find harmonious coexistence amidst the towering trees of Khao Kradong.

The land clearly belongs to the villagers. It’s their heritage, and it’s wrong for big corporations to just swoop in and take what isn’t theirs.

I disagree, Joe. Legal documents and the Supreme Court support the SRT’s claim. We can’t ignore the law because of sentimentality.

But laws should also protect the underprivileged. The government made an error before, and it should correct it now.

It’s true, Joe. If we let big companies run the show, what’s left for ordinary citizens?

Why isn’t there a solution that benefits both parties? Maybe they can lease the land like others have done in the past.

Leasing sounds like a compromise, sure. But rightfully, the SRT should own the land before leasing.

Leasing is only a temporary fix. We need a more sustainable solution for real change.

Exactly, Nancy. These villagers are the backbone of the community. They deserve justice!

Honestly, local state agencies should have a bigger say. They know the ground reality better than anyone in Bangkok.

That doesn’t excuse them from following national law, Sanjay.

Decentralizing such decisions might actually bring better justice and efficiency.

These disputes are all too common in Thailand. It’s about time we standardize the processes to avoid such conflicts in the future.

Standardization is tough with so many variables at play. Each case has unique factors.

Khao Kradong’s beauty shouldn’t be marred by human greed. Preservation should come first, not profit.

Villagers have plowed these lands for generations. How can someone now say it’s not theirs?

The past alone doesn’t dictate legal land ownership.

What worries me is how such disputes often affect community morale. People aren’t just losing land, they’re losing their unity.

If the state rail can’t prove proper acquisition, the land should stay with the villagers.

This isn’t just about crop land. It’s about maintaining links to our heritage.

Songsak’s stance shows that at least some officials recognize the villagers’ plight. That’s promising.

Yes, Polly. It’s heartening to see officials taking a stance for the people, not just bureaucracy.

In many such cases worldwide, we’ve seen that only thorough investigations can bring lasting solutions. No quick fixes here.

True, but thorough means timely. We can’t drag this on forever.

It’s ironic how land struggles occur on such sacred grounds. Preservation of nature should be prioritized.

Once the Supreme Court gives its verdict, we should respect their decision. That’s what rule of law means.

True, Angela, but legal decisions must also account for social justice.

I just hope whenever the decision is made, the people’s voices are heard loud and clear.

Simple really, if their claims are true, the villagers should be moved and compensated for development. Both parties win.

Why uproot people from their homes when it’s clear they have historic rights? Justice seems one-sided.

Sometimes relocation is the only viable option, despite how tough it sounds.