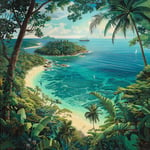

A recent visit to the beautiful island of Koh Kut by Deputy Prime Minister Phumtham Wechayachai turned what should have been a serene survey into a diplomatic drama involving an old, seemingly never-ending, maritime dispute. On that sunny Saturday, Phumtham and his entourage boarded a ship to inspect the historically contentious waters in Trat province. While there, he sought to reassure all Thais, both on the island and off, that the sovereignty of Koh Kut remains firmly under Thailand’s jurisdiction, despite old treaties and rival claims that seem to resurface like a tenacious seaweed.

The drama unfolds around a 2001 memorandum of understanding (MoU) signed under the Thaksin Shinawatra administration. Designed to be a simple mechanism to address overlapping maritime claims between Thailand and Cambodia, this MoU has become a hot potato in political circles. Many believe it consigned part of Thailand’s sovereignty to oblivion, a claim Phumtham vehemently dismisses. “Koh Kut has always been a part of Thailand,” he stated emphatically. “Our fellow Thais live and work here, and our government offices have long established their presence.”

Nevertheless, some political figures and parties, particularly Thai Pakdee Party’s outspoken chairman Warong Dechgitvigrom, aren’t swallowing that line. His demand for the MoU’s nullification isn’t just about words—he’s on a mission to collect 100,000 signatures to bolster his case. Yet, the government warns that a unilateral pullout might do more harm than good, potentially stirring an unwelcome diplomatic pot with Cambodia.

This brewing pot has caught the attention of the Palang Pracharath Party as well, led by Gen Prawit Wongsuwon, echoing Warong’s calls to tear up the agreement. Despite these political ripples, Phumtham remains resolute, insistent on Thailand’s dominant narrative. “It’s being blown out of proportion due to a mix of hearsay, misinformation, and downright fake news,” he quipped, attempting to clear the fog of confusion rolling over this scenic dispute.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra is advocating for a Joint Technical Committee to tackle these murky maritime claims pragmatically. Plans are underway for potential negotiations that promise “win-win” outcomes. Still, not all voices are in harmony. Dr. Warong suggests a prerequisite: that Cambodia should ratify the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) before any cross-border tête-à-tête can commence. Without this formal nod, Cambodia could craftily sidestep obligations in future negotiations, complicating the maritime dialogue further.

The 2001 MoU fascinatingly compartmentalizes the overlapping claims area (OCA) into dual regions—the upper part awaiting boundary talks, and the lower part pegged for joint developmental ventures. Warong finds the Prime Minister’s understanding of Cambodia’s territorial ambitions somewhat naive, especially regarding the unexpectedly detoured boundaries around Koh Kut. “It’s a crafty design for joint energy resource claims,” he suggested, reading between the legal lines scribbled over maritime maps.

Amongst the clamor, Thaksin popped his head into the narrative from Bangkok, clarifying the MoU’s non-binding nature. Though merely a guideline, it carries weight under international law, sometimes as burdensome as the Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907. While some have sought to entangle the treaty with Thaksin’s personal ties to Cambodia’s power corridors, he insisted they’re as different as night and day. “Back in the day, during the embassy riots, I prioritized Thailand’s interests, even when my friendships extended across borders,” he asserted, turning an old anecdote into a pledge of loyalty.

While Thaksin’s days advising Cambodia on economic matters are long past, his political shadow stretches across this historical impasse. As the waves of contention roll on, Thailand’s leadership, both past and present, finds itself once again navigating the tricky waters of international diplomacy, trying to chart a course as smooth as Koh Kut’s tranquil beaches, less troubled by the tides of uncertainty.

I can’t believe we’re still fighting over this. Koh Kut is obviously part of Thailand! Why can’t Cambodia just let it go?

It’s not as simple as that, Joe. Historical claims can be very complex, and both sides need to reach a diplomatic solution.

Maybe so, but Thailand has been in control for ages. What’s next? Are they going to claim Bangkok too?

The real question is whether borders decided by colonial powers should still hold today. Isn’t it time for regional cooperation rather than conflict?

Joe, if Cambodia also feels strongly about it, they won’t let it go so easily. International politics are about negotiations, not just claims.

Phumtham is right. Fake news is making this worse than it is! Diplomacy over drama, people!

But at the same time, transparency is key! If there’s any shady deal in the MoU, that should be clear too.

Not everything is fake news, though. Some concerns are legit, especially when it comes to national sovereignty.

If we nullify the MoU like Warong wants, couldn’t that just lead to more tension and closed-door deals with Cambodia?

That’s exactly what the government fears. Breaking agreements can lead to diplomatic backlash.

I agree with Warong. If the agreement isn’t in Thailand’s best interest, why keep it?

It’s intriguing how Thaksin characterizes the MoU as non-binding yet praises its diplomatic weight. Playing both sides?

That’s politics for you. Portray something as crucial and dismiss it as insignificant all in one breath.

Or maybe he’s just trying to cover for past mistakes? Still, he did prioritize Thailand back then.

Why do we even entertain oil and gas joint ventures in disputed territories? Isn’t that just asking for trouble?

Because the potential profit can outweigh the risks for both countries. It’s tricky politics but potentially lucrative.

Environmental impact is often overlooked in these discussions too. Energy resources at the cost of marine life!

I think a Joint Technical Committee is proactive. But what if negotiations fail without an UNCLOS ratification?

Then we get more rounds of diplomatic skirmishes and public outcry. Both countries need to be committed.

Hasn’t Cambodia’s lack of UNCLOS ratification been an issue before? Seems like they’re avoiding responsibility.

It’s true. UNCLOS would set clearer rules, but some countries prefer ambiguity for negotiation leverage.

As an outsider, all these territorial disputes sound like petty squabbling. Can’t ASEAN mediate?

ASEAN often avoids meddling unless invited—it values non-interference. Internal pressure may work better.

I’m worried about international law implications. Doesn’t the Franco-Siamese Treaty still haunt our diplomatic matters?

Warong can pursue this signature collection, but without the broader public’s support, it may not hold up long-term.

Raising awareness is key, and if Warong thinks this a critical issue, more power to him. But it should be fact-based.

Public opinion is just one part of the political puzzle. Legal and diplomatic processes are another.

Phumtham’s approach seems level-headed amidst the chaos. Haven’t we learned anything from past regional tensions?

Phumtham versus Warong in this debate shows how divided our politics can be even within one country.

What about the tech for boundary disputes? Satellite and drone tech could provide objective data. Why isn’t it used more?

It’s nice to see politicians like Gen Prawit echoing the people’s sentiment. But should military figures be pushing diplomatic agendas?

That’s always the question, Patty. Diplomacy should be led by civilian agencies. But influence counts too.

We shouldn’t just talk about boundaries and politics—what about the local communities on Koh Kut? Their voices matter too.