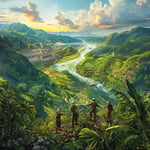

Picture an idyllic stretch of the Mekong River, flanked by the lush landscapes of Laos, where nature seems to hum in harmony. But looming on the horizon is a titanic vision, a project that has sparked tangled controversy across borders: the Pak Beng hydropower dam. This behemoth of a project is set to become a cog in Laos’ ambitious plan to turn itself into “Southeast Asia’s Battery.” At the heart of this is a dam whose intentions are grand, but whose impacts could ripple across the region.

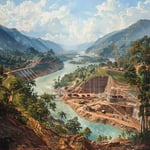

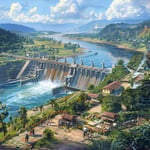

Nestled in the serene land of Pak Beng district in Oudomxay province, a mere 90 kilometers from Thailand’s Chiang Rai, the dam promises to churn out an impressive 912 megawatts of electricity. Stretching over eight years in construction, this powerhouse aims to usher in a new era of energy trade with the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Egat) by 2033. Yet, with the ticking clock, tension rises on the riverbanks as communities brace for the ripples of change.

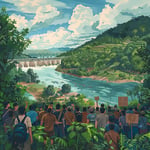

Proponents might hail the dam as a beacon of progress, yet environmentalists are raising alarm bells over adverse impacts creeping into the daily lives of residents on both Thai and Lao soil. The Transboundary Environmental Impact Assessment (TBEIA) is the magnifying glass peering into these potential disruptions. However, the blueprint has walked a contentious road, with critics in Thailand decrying outdated environmental studies and calling out the lack of substantial public engagement.

Pianporn Deetes, steering the regional campaign for International Rivers, echoes these concerns. From her vantage point, despite murmurs of progress, actual construction remains at the fledgling stage, marked mainly by the skeletal framework of access roads and a solitary bridge. In Laos, the shadow of relocation falls heavy as whispers grow louder, foretelling the upheaval of communities to make way for the dam.

Floods, already a scourge of the northern Thai landscape, add a deeper undercurrent of anxiety regarding the dam’s potential to exacerbate these watery deluges. Pianporn points to a mathematical model—an analytical tool civil groups have clamored for—to gauge the flood risk, yet such a model has seemingly been engulfed by silence. Communities lining the Mekong in Chiang Rai—Chiang Khong, Wiang Kaen, and Chiang Saen—fear the creeping waters could push past their riverbanks, swallowing homes and farmland whole.

Legal hurdles stretch across this saga like invisible trip wires. Sor Rattanamanee Polkla, legal eagle with the Community Resource Centre, underscores a critical gap in Thai law—a lack of mandatory transboundary impact assessments, rendering Thai jurisdiction over Lao projects nonexistent. As appeals make their slow crawl through the legal labyrinth, the Supreme Administrative Court ultimately shrugs, acknowledging the limits of governance across borders.

The TBEIA faces scrutiny not just from legal watchers but from those fearful that the raft of concerns—including the impact on Thai communities—will be inadequately addressed under Lao oversight. Sor Rattanamanee’s insights highlight a disquieting uncertainty hanging over the process, casting a shadow on the extent of Thai involvement and influence.

Hannarong Yaowalers of the Thai Water Partnership Foundation adds another layer, advocating for a comprehensive view that peeks beyond the immediate locale in Laos to potential repercussions on Thai soil. Casting a critical eye over the focus of the TBEIA, he insists that the Energy Generating Authority of Thailand must ensure wider assessments—spanning fisheries, natural resources, and societal impacts—find their place within any power purchase agreements.

Moreover, the very necessity of the dam stands questioned. Surichai Wankaew, a Chulalongkorn University professor emeritus, voices a fundamental critique: with a surplus of power reserves, does Thailand truly need this additional generated electricity? The specter of unnecessary investment hovers, fueling further scrutiny from environmental advocates and civil groups.

The Pak Beng project sits squarely in the sights of the Mekong River Commission, an intergovernmental arbiter for Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Yet, advocacy groups continue to lash out at flawed assessments, spotlighting legal holes and insufficient dives into the transboundary impacts touching on environment, health, and social fabrics.

This unfolding drama along the Mekong is a complex dance of power, ecology, and human livelihoods. As the river meanders through its age-old course, those who dwell by its banks watch and wait, wondering what the future holds for their beloved waterway.

Building this dam is a terrible idea! It will destroy the Mekong’s ecosystem and harm local communities.

Absolutely agree! Environmental studies are outdated and dismissive of long-term impacts.

But isn’t it necessary for economic progress? Laos needs development.

How can you say it’s terrible before it’s even fully studied? Let’s see more research.

It’s not just about research. History shows these projects often harm more than they help.

Can we really trust the Lao government to manage the dam responsibly? Seems doubtful.

People keep underestimating how much benefit energy trade can bring to Laos and the region.

That’s true, but do the environmental costs really justify that economic gain?

If managed correctly, yes. It’s a matter of finding a balance between growth and conservation.

Flood risks are a real concern. The government must prioritize those before anything else.

We’ve seen floods before. They don’t care until it’s too late.

Exactly, prevention should be key, not dealing with aftermath.

Honestly, this dam could just exacerbate the power reserve surplus. It’s an unnecessary investment.

I’m on the fence about this. Energy generation is vital but at what cost?

That’s the million-dollar question. We need more information before deciding.

Who profits from this deal? Follow the money, and you’ll find your answers.

Always a hidden agenda when big corporations are involved.

True, transparency is crucial, yet often neglected in projects like these.

I think we should invest in alternative renewable sources rather than dams which cause so much disruption.

Thailand’s legal system seems powerless here. They need jurisdiction on these transboundary issues.

But how can they enforce laws on another country’s projects? It’s complicated.

If fishing is disrupted, countless livelihoods are at stake. We must think of the broader social impact.

It’s frustrating how many hurdles these projects face due to environmental concerns. We need to move forward for progress.

Progress shouldn’t come at the expense of our planet’s health.

Agreed, but everything has a cost. It’s about managing that balance properly.

If only governments were more collaborative in these assessments, we might avoid such contentious debates.

Why not invest in solar or wind, which are less damaging than large scale hydro projects?

Solar and wind aren’t always reliable. Dams provide a stable energy source.

Think of the future generations. We need sustainable choices, not short-sighted developments.

Energy independence for Laos could mean big political gains. That’s likely a major factor here.

It’s easy to criticize from afar. Why aren’t activists on the ground looking for solutions?

I heard some locals are actually in favor of the dam due to the promise of jobs and infrastructure.