In the bustling city of Bangkok, a sanctuary exists where Vietnamese refugees can seek short-term relief from their harried existence, living in a constant state of fear over potential arrest or deportation. This is a product of Thailand’s absence from the UN Refugee Convention, which has left the country without a differentiated approach towards refugees and other immigrants. This lack of clarity has resulted in a multitude of people living somewhat invisibly, under constant threat. Nevertheless, a silver lining appears with the expected introduction of a revamped system, designed expressly to differentiate between individuals who would face peril if returned to their homeland and those who are residing in Thailand unlawfully. This, though, is met with apprehension by refugees and human rights activists who are wary it could be misused, or speed up deportations.

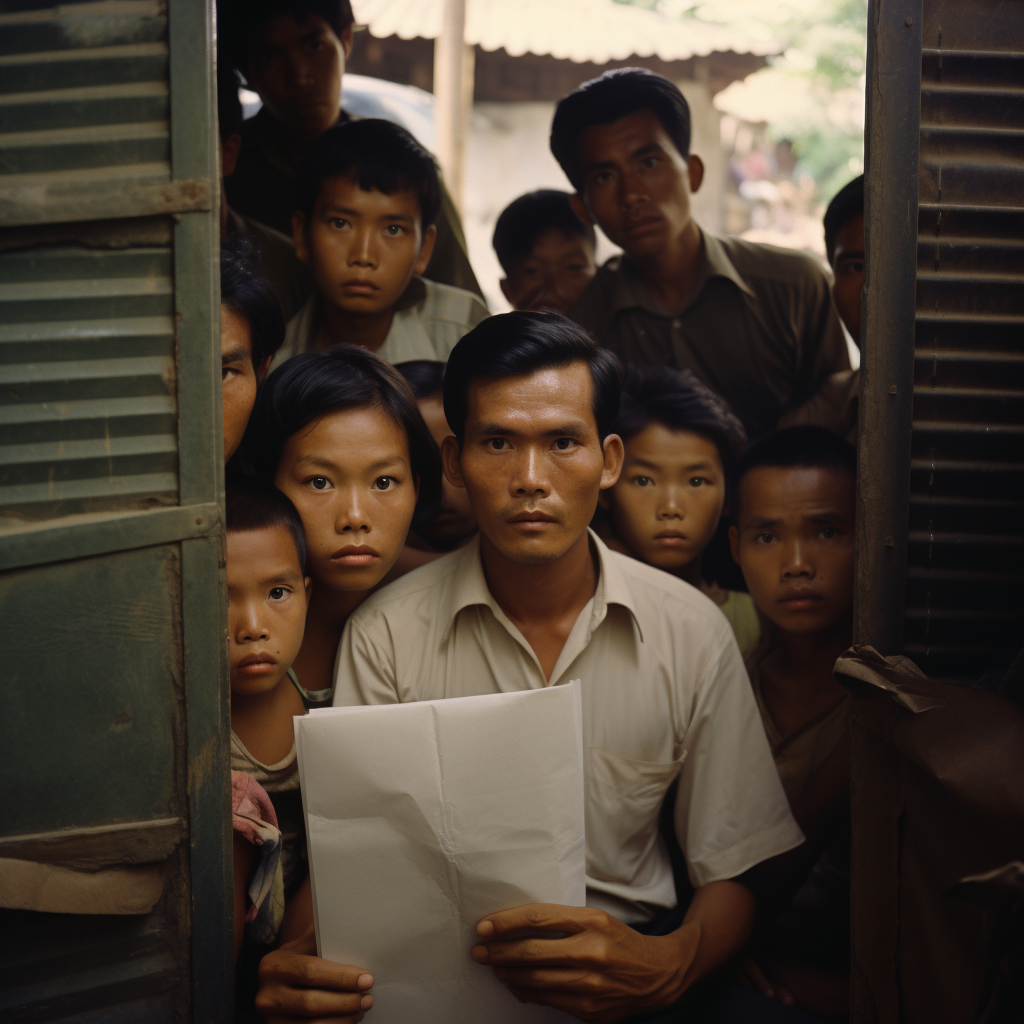

Sung Seo Hoa, a Vietnamese pastor belonging to Vietnam’s Hmong minority, echoes these shared fears. Having escaped from the oppressive communist regime in his homeland over a decade ago, he now subsists within a cloud of fear: “We live in constant fear of arrest by the police, being incarcerated or deported back to Vietnam. We are plagued by this 24 hours a day.” Consequently, he is hesitant to engage with the new screening process, citing the perils it could harbor.

The National Screening Mechanism, scheduled for launch later this month, will inaugurate a regime in which primarily urban refugees and asylum seekers are subjected to scrutiny by Thai police. Those deemed as protected individuals will garner temporary residence permits along with access to healthcare and educational institutions, but without the legal right to work. Yet, apprehensions percolate regarding potential “loopholes” pertaining to national security, which could particularly impact groups like the Uyghurs from China, Rohingyas from Myanmar, and North Koreans, as reported by Bangkok Post.

Phil Robertson, who holds the position of deputy director for Asia at Human Rights Watch, expressed concern over these potential loopholes and the lack of transparency, not to mention the possible abuse latent with the police serving as the screening committee. “There are alarmingly broad and undefined provisions tied to national security that the government could exploit to avoid processing certain individuals as refugees and do so without any explanation necessary,” Robertson elaborates. Concerns are mounting too that the new system could devolve into a pay-to-play situation, wherein individuals with resources can manipulate their way to attaining status. Moreover, the intended screening procedures prominently feature criminal background checks, creating the potential danger of entangling Myanmar anti-coup activists wrongfully accused.

Bearing in mind Thailand’s record of deporting refugees, as evidenced with the 109 Uyghurs deported to China in 2015, there remains a tangible atmosphere of skepticism towards the system, observes Patrick Phongsathorn, of the advocacy group Fortify Rights. “There seems to be a level of cooperation between oppressive governments in this region for targeting each other’s dissenters – a sort of swap shop,” he suggests.

The Thai Department of International Organisations counters these concerns with assurances that privacy and confidentiality are integral tenets of the system and that the principle of non-refoulement would be observed with rejected applicants not being returned to their countries. A system of appeal against rejection has been established, open within a ninety-day window under the refugee system. Whether or not the UN High Commissioner for Refugees will continue conducting screenings under the prevailing system remains to be seen. The agency maintains that it has been collaborating with Thailand in a bid to establish an equitable, effectual, and transparent protection system that aligns with international standards. Stay updated on our latest stories on our new Facebook page.

Be First to Comment