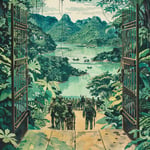

The fighting in Myanmar resumed this week after a fragile five-month ceasefire brokered by China between the junta forces and ethnic minority insurgents apparently unraveled. Ironically, the renewed strife erupted mere days after the global community marked World Refugee Day last Thursday.

By the end of 2023, there were a staggering 117.3 million forcibly displaced people globally, according to the UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency. Of these, an estimated 47 million (40%) were children under 18. Moreover, between 2018 and 2023, 2 million children were born into refugee status, with an average of 339,000 refugee births annually.

Thailand, sharing its longest border with Myanmar, has been a sanctuary for refugees. The escalating conflict in Myawaddy since 2024 has driven tens of thousands, primarily women and children, to seek refuge in Thailand. Given the dire and unwavering situation in Myanmar, these refugees are poised to remain in Thailand for months, if not years. The challenge confronting Thailand and aiding organizations extends beyond merely providing food and shelter; they must also equip these refugees for future resilience. For young refugees, the need surpasses sustenance and safety—education is paramount.

Thailand’s policy of “Education for All,” outlined in a cabinet resolution passed on July 5, 2005, grants all children within Thailand, regardless of legal or national status, access to the education system up to the doctoral level. This laudable policy promises 15 years of free education, from kindergarten through Mathayom 6 (Grade 12), to all migrant children, with per-student budget allocations equal to those for Thai nationals.

This policy has garnered accolades globally, yet ground-level execution remains riddled with challenges. Numerous schools still deny entry to these children or impose prerequisites such as Thai language proficiency tests and additional fees.

Data from the Coordination Center for Education of Migrant Children and the Tak Primary Education Service Area Office 2 as of March 2024 indicated at least 64 learning centers catering to over 15,139 migrant students. However, this number falls short of addressing the burgeoning influx.

In addition to insufficient support, migrant learning centers face the threat of raids. Last year, migrant primary school students in Ang Thong and Lopburi provinces were sent to Chiang Rai for repatriation, blatantly disregarding their safety and right to education.

In February, the Office of the Basic Education Commission (OBEC) issued a directive mandating all state primary schools to enroll migrant children irrespective of documentation. Nevertheless, the regional education office in Tak defied this by continuing to bar migrant children from attending school.

This defiance not only contravenes the “Education for All” policy and directives from their superiors but also opposes Thailand’s highest law. According to Section 54 of the constitution, the government is obligated to provide education for every child within its borders.

Denying children their right to education renders them susceptible to labor and sexual exploitation, human trafficking, and juvenile delinquency. The Education Ministry and OBEC must ensure that renegade education officials are held accountable for exacerbating the plight of these vulnerable children and worsening social issues.

Moreover, there must be increased support for migrant learning centers to ensure that both migrant and war-displaced children receive an adequate education. Only then can these children hope to carve a brighter future amidst the shadows of conflict.

It’s commendable that Thailand has an ‘Education for All’ policy, but if schools are still denying entry to migrant children, what’s the point? It’s just lip service!

True, Jenny. Policies are only as good as their implementation. The government needs to crack down on schools flouting the rules.

Crack down how? It’s not like Thailand has unlimited resources to enforce every little rule in every remote school.

Sara, enforcing a law that affects thousands of vulnerable children isn’t a ‘little rule’. Prioritizing it may be tough, but it’s necessary.

I agree with you both. However, don’t forget that local communities are also under immense pressure, and the influx of refugees isn’t easy to manage.

Education is important, but how can Thailand afford to provide top-notch education to refugees when its own system struggles?

Mark, it’s about basic human rights! These kids didn’t choose to be refugees. A society is judged on how it treats its most vulnerable.

Mark raises a valid concern. While it’s crucial to educate these children, we also need robust international support and funding to make it feasible.

True, Kara and Prof. Harris. Global partnerships and financial aid can help. But let’s be honest, the world isn’t always this altruistic.

Raiding schools for migrant kids and sending them back is downright terrifying! Isn’t there something Thailand can do to prevent these inhumane practices?

Education raids violate not just national policies but basic human decency. There needs to be harsh punishment for those involved.

Agreed, Liam. But punishing individuals won’t solve the root problem. There’s a systematic issue that needs addressing.

Exactly, Grace. Policy change is essential, but so is public awareness and community support to create real change.

Why is it always about education when these kids can barely get food and shelter? Priorities, people.

Sophia, education IS a priority. Without it, these kids have no future. It’s not mutually exclusive with food and shelter.

Emily has a point. Long-term resilience means empowering these children academically. It’s a critical part of the support system.

This issue needs international coverage and pressure to be solved effectively! The local government alone can’t handle it.

Sad truth, Leo. But getting global attention isn’t easy. There’s so much conflict worldwide; Myanmar’s crisis gets buried under other news.

Chloe, true. We need more NGOs and international bodies making noise about this. It’s our responsibility as global citizens.

Isn’t it ironic that this blows up just after World Refugee Day? It’s as if the world only pretends to care for a day.

How can we in other countries help? Donating to charities? Raising awareness? The situation feels so helpless.

Amanda, start with reputable NGOs. Public pressure via social media can sometimes make a difference too.

As a teacher, hearing about kids being denied education is heartbreaking. What can we do to support educators in Thailand?

If the Thai government won’t step up, maybe international bodies should impose sanctions or take legal actions.

James, imposing sanctions can sometimes make things worse for the people you’re trying to help. More practical support solutions are necessary.

True, Helena, but there’s got to be accountability. Otherwise, the cycle of neglect continues.

I think local Thai communities could be better educated on the importance of integrating refugees. Fear and misinformation often fuel opposition.

Great point, Patricia. Grassroots change can sometimes be more effective and sustainable than top-down policies.

Volunteers and social workers play a key role in bridging the gap where the government falls short. Community initiatives can make a big difference.