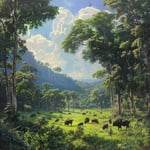

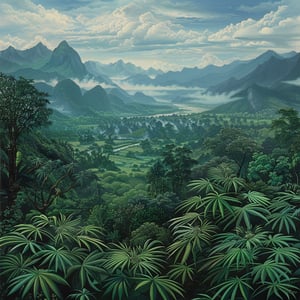

Deep in the heart of Thailand’s majestic forests, an ancient ballet unfolds. The serene green expanses of Khao Yai National Park and its neighboring Khao Phaeng Ma Non-Hunting Area occasionally play host to some quite astounding visitors. These are the gaurs, wild and mighty, stepping out of the foliage in search of sustenance. But as enchanting as their presence might be, these powerful creatures have inadvertently found themselves in the headlines for all the wrong reasons.

In the picturesque but increasingly tense district of Wang Nam Khieo, local tourism businesses are sounding the alarm over a recent spate of human-gaur encounters that are growing increasingly close for comfort. Picture the scene: a mother and daughter, enjoying a tranquil motorbike ride along Highway No 3052, suddenly find their journey turned on its head by a bull gaur in high dudgeon. The gaur, agitated and likely hungry, doesn’t just cross their path—it charges. Their motorbike becomes a twisted metal casualty along the asphalt, while the gaur takes the young girl on an unexpected detour into the wilderness, her mother in desperate pursuit. Thanks to the mother’s heroics, a forest 100 meters deep offered back the girl, shaken but alive, paving her way to the safety of hospital care.

It’s Saturday, and the Wang Nam Khieo tourism club is in session, a scene of earnest discussion and resolute decision-making. In their eyes, this situation is not just unfortunate—it’s untenable. They’re rallying for changes, advocating for the glow of more streetlights to pierce the dark, treacherous stretches of road where gaurs roam and tyres tread with uncertainty. They suggest buffet zones within Thap Lan and their own Khao Yai National Parks, bursting with flora to feast on, hoping it will keep the gaurs happily grazing within rather than foraging further afield.

The club has noted the surging population of these giant herbivores, understanding that the issue at heart is a simple one—hunger. With insufficient natural supplies to meet the demands of growing appetites, the gaurs are embarking on new, dangerous migrations. In their statement, they plead, “For the harmonious coexistence of human and animal kin, these strategies must unfurl with haste.”

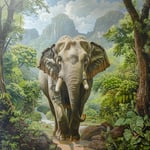

Meanwhile, Annop Buanuan, custodian of the park, traces the footprints of the wayfaring gaur, linking his unexpected journey to the ceaseless quest for food. To counter the migration, low-voltage fences spring up, a feeble defense against the pressing scarcity driven by the parched season. Prawattisat Chantharathep, guardian of Thap Lan National Park, can only nod in agreement; the menu in the wild has indeed been shrinking.

To understand the depth of the issue, you need only peruse the numbers—around 300 gaurs, those impressive icons of wild strength, calling Khao Phaeng Ma’s steep slopes their dining room.

The veterinarian Phattharaphon Mani-on may spend his days amidst the beauty of wildlife, but he knows that when animals and humans collide, the outcome is rarely picturesque. Elephants in the living room are problematic, but gaurs on the highway are a statistic that carries a graver weight—11 unnerving incidents in just three years.

Finally, we return to Mr. Annop who, as a closing statement of defense and caution, issues a sobering edict—drive slow, 20 kilometers per hour if you must, because out here where the wild things are, even warning signs can get swallowed by the night.

Be First to Comment