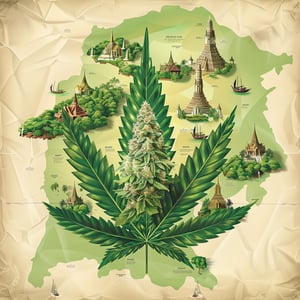

Thailand is a country that packs entire ecosystems into bite-sized provinces: mist-draped highlands, dripping evergreen jungle, thunderous cascades and impossibly blue seas framed by towering limestone cliffs. Wander through its national parks and you’ll find dramas of nature unfolding in every direction — perfect for photographers, hikers, snorkelers and anyone who likes their adventures with a side of jaw-dropping scenery. Here are five parks, one from each region, that capture the wild spirit of Thailand and deserve a top spot on your itinerary.

North — Doi Inthanon National Park (Chiang Mai)

Nicknamed “The Roof of Thailand,” Doi Inthanon crowns the country at 2,565 metres above sea level and serves up cool air, cloud-swept forests and the kind of sunrise views that make you forgive the early alarm. The summit is just the beginning: waterfalls like Wachirathan and Mae Ya thunder down rocky faces into emerald pools, perfect for picture breaks and quiet picnics.

Birdwatchers will feel like kids in a candy store: roughly 500 bird species have been recorded here, and the highland flora includes plants that thrive only in this cool, humid climate. A cultural highlight is the twin Royal Chedis near the peak, built to honor the 60th birthdays of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej and Her Majesty Queen Sirikit. At golden hour, clouds spill over distant ridges and the chedis glow — the kind of view that makes you breathe slower and smile wider.

Best time to visit: November–February for crisp, low-rain conditions ideal for hiking and photography.

East — Mu Ko Chang National Park (Trat)

More than 40 islands dot Mu Ko Chang, a marine playground in the Gulf of Thailand where jungle-clad mountains tumble into secret coves. Ko Chang — the main island — blends rugged hiking with wallet-friendly beach downtime: scramble jungle trails to find secluded bays, then trade your hiking boots for snorkel fins in crystalline water.

The marine reserves here harbor vibrant coral gardens and abundant fish life, and viewpoints like Khao Salak Phet (about 744 metres) reward the sweaty climb with sweeping ocean panoramas. If you’re after a blend of adventure and serenity, Mu Ko Chang is a perfect fit.

Best time to visit: December–April for calm seas, sunny skies and excellent snorkelling visibility.

West — Erawan National Park (Kanchanaburi)

Erawan is the waterfall lover’s dream, centered on a spectacular seven-tier cascade whose pools range from postcard-blue to deep emerald. The falls are named after Erawan, the mythic three-headed elephant, because the top tier’s cliffs resemble the creature’s spouts — poetic and true.

Trails thread through primary evergreen forest, shaded and cool, where each bend can reveal a fresh swimming hole or a friendly troop of forest birds. Walk each tier at a leisurely pace, dip into those cool pools and let the rainforest soundtrack do the rest.

Best time to visit: November–January when the weather is dryer and cooler, making waterfall treks more enjoyable.

Central — Khao Yai National Park (Nakhon Ratchasima)

Khao Yai is classic Thai wilderness — sprawling, biodiverse and a magnet for wildlife enthusiasts. Part of a UNESCO World Heritage Forest Complex, the park is home to elephants, gaur (Indian bison), gibbons and hornbills, and it’s one of the best places in Thailand to spot large mammals in the wild.

Trails and access roads lead to hidden waterfalls like Haew Narok and the iconic Haew Suwat (yes, the one from the movies). For a dash of nocturnal excitement, join a guided night safari and watch the forest reveal its other face under the stars, when owls, civets and other night-shift animals make their rounds.

Best time to visit: November–February for the crispest air and highest chances of daytime wildlife sightings.

South — Hat Noppharat Thara–Mu Ko Phi Phi National Park (Krabi)

If you’ve ever dreamt of a classic tropical postcard, Phi Phi delivers the real thing: powder-white sand, turquoise water and dramatic limestone karsts jutting vertically from the sea. Within the park, Maya Bay’s sheltered cove, Ko Poda’s vibrant snorkel sites and Hat Noppharat Thara’s long crescent beach all headline the island-hopping circuit.

Don’t miss geological wonders like Viking Cave, with its ancient cliff art and swiftlet nests, or the Three Islands (Talay Waek), where sandbars connect islands at low tide — a natural spectacle that invites a barefoot stroll. For a bit of elevation, the Khao Ngon Nak Nature Trail offers a strenuous climb with sunrise and sunset panoramas worth every sweaty step.

Best time to visit: November–April for calm seas, good visibility and optimal diving conditions.

Together these five parks showcase Thailand’s extraordinary range: mountain mists, jungle shadows, thunderous falls and crystalline seas. Whether you’re chasing wildlife tracks at dawn, plunging under a waterfall or drifting over coral gardens, Thailand’s national parks are waiting with something remarkable around every bend. Pack a camera, lace up your boots, and prepare to be pleasantly lost.

Author here — glad you read the piece. I tried to balance practical tips with conservation notes, but I know the overtourism debate is complicated.

Nice article, but can we stop promoting places like Phi Phi until they fix overtourism and reef damage? Turning nature into a postcard is killing it.

Sophie has a point; repeated boat anchor damage and sunscreen-linked bleaching are documented problems in Andaman reefs, and policy responses have lagged behind visitation spikes.

Totally agree that some sites need stricter limits; my intent was to highlight options across regions, not to encourage unregulated mass tourism. I’ll add more notes about sustainable operators and low-impact seasons next edit.

I visited Doi Inthanon last year and the chedis were beautiful at sunrise, but the trails were crowded. How do you suggest avoiding the crowds while still supporting local guides?

Go midweek in shoulder season and hire a local guide from a village — they tip better and know quiet routes. That helps the economy without adding traffic to park entrances.

Looks amazing, but isn’t it hypocritical to fly across the planet to ‘save’ nature by taking pictures? Feels like nature tourism is just self-congratulatory consumption.

I get that critique, but responsible tourism funds conservation and livelihoods for locals who might otherwise sell land to destructive industries.

That’s true sometimes, but the money often leaks to big tour companies. We need transparent fees and community-managed access, not just platitudes.

I’d rather see sustainable transport options promoted — trains, longer stays — instead of the endless short-hop tourism that burns fuel for quick Instagram shots.

Khao Yai’s mention of gaur and elephants is accurate, but anyone going should be briefed on human-wildlife conflict protocols; these animals are increasingly stress-impacted by roads and lights.

As a ranger’s nephew, I can confirm night safaris are popular but sometimes disruptive; guided nocturnal walks need stricter guidelines and smaller groups.

Exactly — smaller group sizes, quiet gear, and route rotation can reduce disturbance. Park management plans should enforce that.

What about criminal enforcement? Are penalties for illegal logging and poaching enforced, or is it mainly performative?

Erawan looks dreamy but I’ve read some tiers have been closed intermittently to recover. Tourists need to respect closures; swimming everywhere isn’t harmless.

I swam at the lower tiers last year and saw trash and plastic bottles near the trailhead. People talk about conservation but bring their trash anyway.

Local businesses should be required to provide trash bins and education; it’s a shared responsibility, not just tourists’ fault.

Why no mention of access for disabled travelers? National parks often ignore wheelchair access and accessible trails, which is a major oversight.

Great point — inclusive infrastructure is rare in many parks, and advocating for accessible viewpoints and transport should be a priority in articles like this.

As a traveler who uses a cane, I second this — trail conditions are often poorly signposted, and some ranger offices can provide assistance if contacted in advance.

Mu Ko Chang sounds perfect for snorkeling, but how safe is it for solo female travelers? I worry about both marine hazards and on-shore safety.

In my experience, small islands can be very safe if you choose family-run guesthouses and avoid isolated bars at night. Local guides are usually trustworthy.

Always tell the guesthouse your plans and ask about tide charts and currents before snorkeling; local fishermen often know dangerous spots that aren’t on maps.

As someone from Nakon Ratchasima, I love Khao Yai but resent how small roadside eateries get crushed by tour buses bringing only day-trippers.

Day-trippers are the worst for local economies; they spend little and leave big footprints. Incentivize overnight stays with promotions to help locals.

Exactly — overnight stays spread income and build respect for local customs. Parks should partner with nearby villages on homestay programs.

Hat Noppharat Thara–Mu Ko Phi Phi is stunning, but I worry about privatization of beaches and exclusionary policies that push out fisher communities.

Coastal privatization often undermines traditional marine stewardship. Community-based marine protected areas have better long-term outcomes than top-down bans.

So what’s the solution? Force companies to hire locals? Charge higher fees and funnel them to communities? We need practical fixes, not just criticism.

I’m in 6th grade and I want to see elephants and big waterfalls. Is it true you can swim at every waterfall? It sounds like an adventure!

Not always — some tiers are unsafe or closed to protect wildlife. Always check ranger notices and never swim in strong currents even if it looks calm.

Why are national parks always marketed only for photos? There should be more emphasis on long-term learning trips, volunteer programs and research stays.

Volunteer programs can be great, but they must be well-regulated; unskilled volunteers sometimes do more harm than good if projects aren’t community-led.

The article romanticizes sunsets and chedis but doesn’t discuss how climate change is shifting species ranges in Doi Inthanon and other highlands.

Good catch — montane species are indeed losing habitat area as temperatures rise, and cloud-forest specialists are particularly vulnerable to upslope squeeze.

I’ll update the piece to mention climate impacts — thanks. We should be explicit about how shifting climates change best-visit windows and conservation priorities.