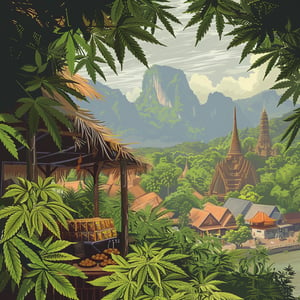

In a grand display of precision and heroism, the skies above the lush, verdant landscapes of Thailand’s northern provinces became the stage for an extraordinary mission. Here, an air force plane, the venerable BT-67, took to the heavens, weaving through the air with a singular purpose: to confront the raging bushfires that threaten the region every summer. Its mission? To identify the fiercest hotspots and unleash torrents of water from above, laying the groundwork for ground operations to extinguish the infernos. This aerial ballet, orchestrated by the Royal Thai Air Force, was but the beginning of an epic battle against nature’s fury.

Meanwhile, on the ground, a storm of a different kind brewed in the political arena. Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin found himself navigating through a haze of controversy and concern. Chiang Mai, a jewel in the crown of Thailand’s tourism sector, was choking under the weight of an air pollution crisis. Yet, in a move that raised eyebrows and fueled debates, the government stepped back from declaring this beloved province a disaster zone. The reason? A fear that such a declaration would tarnish the province’s image as a tourist paradise, sending foreign visitors—and their wallets—scurrying away.

Taking to the digital soapbox that is X, Mr. Srettha defended his administration’s cautious approach. He had, he explained, lent an ear to a chorus of voices, weighing the insights of various stakeholders. The verdict was clear: branding Chiang Mai a disaster zone was not the answer. Such a label, he argued, could deter the waves of international tourists, especially those whose travel insurance turned its back on disaster-struck destinations. Instead, the Prime Minister pledged to explore alternative pathways through the smog, seeking solutions that safeguarded the livelihoods of the populace.

In a further testament to the government’s commitment to this cause, Mr. Srettha triumphantly announced an unprecedented financial boon for the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation (DNP). A budget, grander than any allocated before for disaster mitigation, was approved to empower the DNP in its fight against the wildfires. This financial injection marked a historic departure from past practices, signaling a newfound governmental resolve in tackling the environmental crisis.

But the decision not to declare Chiang Mai a disaster zone has not been without its critics. The province’s air quality, a grim theatre of smoke and particles, sank to levels that ranked among the worst globally. The public outcry was palpable, a smokescreen of frustration and concern. Yet, within these swirling debates, a consensus emerged among tour operators, who rallied behind the government’s stance. They, like Mr. Srettha, foresaw the economic fallout of a disaster declaration, opting instead to brave the murky air in hopes of a brighter tomorrow.

Panlop Sae Jiew, a leading voice in the tourism sector and chairman of the Tourism Council of Chiang Mai, added his perspective to the mix. On the digital walls of Facebook, he painted a picture of resilience and hope. Between March 1-16, he proclaimed, Chiang Mai had welcomed over 52,000 souls, whose journeys infused the local economy with more than one billion baht. In his view, to label the province a disaster zone would be to turn off the tap of tourism, leaving the economy to parch under the shadow of unresolved dust pollution.

Meanwhile, the specter of PM2.5 pollutants cast a long shadow across the kingdom, with 42 provinces ensnared in its grasp. The North, in particular, bore the brunt of this crisis, with all 19 provinces reporting hazardous levels of fine dust. Mae Hong Son emerged as the epicenter of this environmental ordeal, recording a staggering 294 microgrammes per cubic metre of PM2.5—a figure that crowned it the most afflicted in the north.

In this tale of fire and smoke, of politics and economics, the people of Thailand—and particularly those in Chiang Mai—find themselves at a crossroads. As they gaze towards the future, they are left to ponder the price of paradise, and the choices that must be made to preserve it. Amidst the ashes and the airwaves, the battle continues, a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the enduring allure of the Land of Smiles.

This is shocking! I had plans to visit Chiang Mai next month. Should tourists reconsider their plans given the pollution crisis?

I was there last week. The situation isn’t ideal, but it’s manageable with masks. Plus, the local businesses could really use the support.

Supporting an economy shouldn’t come at the cost of our health. The government needs to fix this, not tourists.

Definitely rethink it. Safety first! Also, it’s about sending a message that we won’t tolerate destinations that aren’t taking their environmental impact seriously.

Thanks for the insights, everyone. It’s a tough decision, but health and environmental integrity should come first.

Srettha Thavisin’s strategy seems shortsighted. Tourism revenue won’t matter if there’s no beauty left to visit or clean air to breathe. It’s a band-aid solution on a bullet wound.

You have to consider the economic impact, though. Immediate disaster declarations can harm more than just tourism. It’s about finding a balance.

A balance, yes, but not at the expense of long-term environmental health. There must be sustainable strategies that don’t just kick the can down the road.

As a resident of Chiang Mai, the situation here isn’t black and white. We depend on tourism, but also, the smog is unbearable. There’s no easy solution.

Respect to you and the people of Chiang Mai. Hoping for a resolution that helps everyone.

The additional funds for the DNP sound promising. Clearly, Srettha is planning for a long-term fix, not just a short-term avoidance of the issue.

Promises, promises. We’ve seen allocations before with little to show for it on the ground. I’ll believe it when I see the improvements.

Why is nobody talking about the local farmers and their slash-and-burn practices? That’s a significant part of the problem here!

That’s a common misconception. Studies show that while those practices contribute, the vast majority of the pollution originates from other sources including urban activities and industrial emissions.

Interesting, I didn’t know that. Thanks for the correction! We should focus on those major sources then.

Then please explain why we only have polluted skies during two or three months each year. Is there no traffic the rest of the year? Do industrial plants only operate during smoke season? However I do believe you are correct that the burning of fields is only part of the problem. Here in the north, much of that burning is of corn crop stubble. That could be changed with education about no-till methods of farming, where the new crop is planted in between the old rows. Not only does it eliminate the need to burn, it’s better for the new crop because the stubble provides nutrients for it. More concerning, IMO, are the cultural practices that are behind the practice of burning. My Thai friends have explained this to me in great detail. There is a certain mushroom that sprouts this time of year, which the locals can sell at market for ฿500 per kilo. It is an important source of income for them. The problem is that it will only grow in forests after a burn has occurred. Secondly, there is a particular vegetable that grows this time of year, which is essential for making a special northern Thai curry that is the traditional Songkran dinner (like turkey and stuffing for American Thanksgiving, or Haggis for the Scots). Again, this vegetable grows only after a burn in a forest has occurred. Thus, villagers set fires in the National Parks so they can later harvest these items.

I believe in the resilience of Chiang Mai and its people. This challenge can be a catalyst for change and innovation in how we deal with environmental crises.

Every summer it’s the same story. When will we learn from history and finally make the significant changes needed to combat this annual crisis?