Trapped by Daily Interest: A Thai Woman’s Desperate Plea for Rescue from Loan Sharks

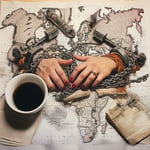

In a story that reads like an economic horror tale, a 49-year-old Thai woman has gone public with a private nightmare: she says she was driven into prostitution — without her husband’s knowledge — to pay 4,200 baht in daily interest to a web of informal lenders. The woman reached out to Channel 3’s Hone Krasae programme, asking journalists and government officials to help untangle the debt spiral that has swallowed her savings, her business and nearly her life.

Once the owner of a small business, she says the pandemic wiped out her income and forced her to turn to loan sharks for emergency cash. She borrowed between 5,000 and 10,000 baht at a time from more than ten informal lenders. What started as short-term loans ballooned into “several hundred thousand baht” in outstanding debt as crippling daily interest mounted over more than three years.

Today she earns a precarious living as a masseuse, offering traditional Thai massage. But the massage shop’s takings are inconsistent — some days she pockets as little as 100 baht, far short of the 4,200-baht interest bill she says she must meet every day. To stay afloat, she admits she sometimes borrows from new lenders to pay off accrued interest, a classic debt-trap tactic that only tightens the snare. When there’s no money at all, she says she avoids returning home and sleeps elsewhere to dodge the consequences of missed payments.

In a wrenching confession to reporters, she said that on occasion she provides sexual services to clients at the massage shop to pay rent and loan interest — a choice she presents as survival rather than desire. Her husband, she says, has no idea about this aspect of her work. When funds run out entirely, she has even begged monks for food to survive.

The woman’s appeal to Hone Krasae was simple and practical: she asked the media to coordinate with government agencies to help negotiate with her creditors so she can repay debts one by one. She stressed that she cannot repay the entire sum at once but wants a structured, manageable plan — a plea for breathing room rather than a miracle cure.

Why this matters

Her case shines a harsh light on a broader social problem in Thailand: the informal lending market. When legitimate credit is inaccessible or small businesses collapse, desperate borrowers sometimes turn to high-interest, unregulated lenders who demand daily payments and use intimidation. The result: households can be pushed to the margins, forced into demeaning or dangerous work, and trapped in cycles of borrowing that seem impossible to escape.

Channel 3 aired her story but did not report any immediate government intervention. For those searching for a formal route to help, the Bank of Thailand recommends contacting the Informal Financial Reporting Centre under the Ministry of Finance. The public hotline is 1359 for consultation — a starting point for anyone dealing with non-bank debt issues.

What could help — and why a public plea matters

A public plea like hers can do several things at once: it humanises the statistics about informal debt, pressures authorities to act, and alerts community groups that might offer legal or financial counselling. If local officials, legal aid organisations or debt counsellors get involved, they can sometimes negotiate reduced repayment schedules, stop abusive collection practices, and connect debtors to relief programmes.

Her stated goal — to negotiate and pay creditors off one by one — is realistic and often the most humane solution in such cases. That approach requires cooperation from lenders, legal oversight to prevent harassment, and support services to stabilise income and living conditions while repayment plans are enforced.

A human face on a systemic issue

Behind the numbers and policy conversations is a simple human story: loss, pride, secrecy and the urgent desire to protect a family. She chose to speak out despite the risk to her reputation because silence had become a sentence. Whether or not officials step in, her story has already done something important — it has given a voice to the many who suffer quietly under the weight of informal debt.

For readers in Thailand who may be in similar straits, the Bank of Thailand’s informal debt hotline (1359) is the official channel recommended for consultation. Beyond that, local NGOs, community legal aid clinics and social services may be able to offer immediate support. For everyone else, her plea is a reminder that economic shocks can turn ordinary lives into desperate ones overnight, and that compassion — paired with practical, coordinated help — can make the crucial difference.

Channel 3’s Hone Krasae spotlighted her plight; now it remains to be seen whether any government department or community organisation will step up to help her rebuild a life that, until the pandemic, she had once managed on her own.

This story broke my heart and it points to a failed safety net in plain sight. Why are people forced into debt slavery while lenders roam free? Someone in government needs to be held accountable now.

She made choices and hid them from her husband; that’s personal responsibility. People keep saying ‘debt trap’ but adults must manage money better.

Calling it personal responsibility ignores predatory practices that charge daily interest and harass families. When interest eclipses income it’s not mismanagement, it’s extortion. We should treat those lenders like criminals, not lecture victims.

Exactly — shaming her won’t fix daily interest rates of 4,200 baht. This is systemic abuse that needs legal and social intervention, not moralizing.

Public pleas like hers are brave and necessary; anonymity often isn’t available to those in debt. The hotline 1359 should be amplified and NGOs funded to negotiate structured repayments.

Hotlines are fine but she hid things from her husband and even turned to prostitution; that’s on her. There has to be some personal accountability here.

Blaming victims misses the point: survival choices under duress are not crimes to be punished socially. Help should focus on protection and financial restructuring.

From a public health and legal standpoint, high-interest informal credit creates predictable harm and risks human trafficking. Thailand needs stronger regulatory frameworks, emergency cash grants, and survivor-centered services to prevent these cascades.

I know someone who fell into the same trap after the pandemic; she couldn’t get a bank loan either. It’s terrifying how quickly the situation spirals.

The article shows how a small-business collapse can become a life-or-death spiral. Does anyone have contacts for legal aid in Bangkok or community groups who intervene?

Local NGOs and community legal clinics sometimes step in but they are underfunded and overloaded. Coordinated media pressure plus legal teams can negotiate one-by-one repayments if lenders agree to stop harassment.

Thanks — I’ll try calling the hotline and reaching out to the clinics mentioned. Media attention helped, but we need on-the-ground action fast.

If these loan sharks are charging 4,200 baht a day they should be indicted and jailed immediately. There is zero place for that kind of predation in a civilized economy.

Yes, but simply jailing collectors won’t fix why people borrow informally: exclusion by banks, lost incomes, lack of social insurance. We need systemic fixes along with enforcement.

Microcredit, community savings, and low-interest emergency funds could be scaled to prevent this. However, implementation needs transparency and anti-corruption safeguards.

I still say enforcement first; stop the bleeding, then reform the system. Survivors shouldn’t endure threats while we talk reform.

Her plan to negotiate repayment one by one seems practical and realistic. Lenders may accept smaller steady payments if pressured and monitored.

Government agencies get calls and do little; community pressure has to be louder. Media stories fade and then nothing happens, leaving people to bargain with thugs alone.

Call the hotline and document every threat, then involve local authorities and NGOs; sometimes publicity plus legal notices makes lenders back off.

This case exemplifies structural financial exclusion and the shadow economy’s role in deepening inequality. Policy responses should include targeted emergency cash transfers, credit access programs, and strict regulation of informal lenders.

That’s so sad. Why didn’t she just go to a bank instead of loan sharks?

Banks often have paperwork, collateral, and credit history requirements that small entrepreneurs can’t meet, especially after income shocks. That’s why informal markets thrive and why public policy must bridge that gap.

Community savings groups could be revived as an interim solution, but they’d need capital and governance support to scale.

We should stop stigmatizing sex work; when she offers sexual services it’s a survival strategy forced by predatory debt. Empathy and protection are priorities, not shame.

Banks extend credit when customers meet criteria; informal lending is a symptom of broader market dynamics. The formal sector can offer options but borrowers must engage with official channels.

Pointing to banks like that’s enough ignores the structural barriers and power imbalance. Empathy for survivors and legal protection from extortion should come first.

Law enforcement must act; sleeping elsewhere to avoid collectors is a crime against human dignity. Authorities can’t hide behind ‘it’s complicated’ when lives are at stake.

Victims should preserve evidence: call logs, messages, threats, and any payment receipts, then contact the hotline and local legal aid groups. We can sometimes obtain injunctions and negotiate temporary relief while pursuing criminal charges.

How can someone without documents or stable housing safely approach authorities without retaliation though? That’s my fear. It seems dangerous.

Confidential services exist and they can protect identities; community groups can help with safe reporting. The state must ensure anonymity and protection for complainants.

I worry that publicizing her identity could endanger her more than help her. Media exposure sometimes invites harsher retaliation by lenders who feel threatened.

Publicity is a double-edged sword: it can mobilize resources and pressure, but it must be managed with security protocols. Long-term solutions need banking inclusion and social insurance, not just headlines.

Then set up anonymous negotiation channels through NGOs; don’t expose vulnerable people to further harm for the sake of a story.

The pandemic didn’t just wipe incomes, it exposed how thin many households’ buffers are. We should have expected more of our institutions to step up, but they didn’t.

This reads like excuses for bad choices; if you can’t run a business you shouldn’t take risky loans and put your family at risk. Tough love matters.

Tough love won’t stop a violent collector at your door or erase daily interest that outpaces your earnings. Structural solutions and emergency relief are what prevent desperation.