This week, the Ministry of Public Health made headlines by announcing a policy shift that stirred quite a bit of conversation. The government decided to lift the longstanding sales restrictions on alcoholic beverages – a ban traditionally enforced daily between 2pm and 5pm, as well as on Buddhist holy days. Such a decision might initially seem at odds with the ministry’s ongoing campaign to curb non-communicable diseases (NCDs) as a top national priority. But let’s delve deeper into the story behind the numbers and the narrative.

The Public Health Minister, Somsak Thepsutin, recently took the stage at an NCD awareness event to address these concerns. His words painted a rather stark picture: approximately 400,000 lives are claimed annually by non-communicable diseases in Thailand, making up a staggering 74% of the nation’s death toll. These maladies – cancer, heart conditions, diabetes, and chronic respiratory issues among them – aren’t just health concerns. They represent a looming economic burden, straining resources and productivity. In 2019 alone, the fallout from such illnesses translated to a jaw-dropping 1.6 trillion baht in economic losses, with expenditure of 1.39 billion baht just on treatments.

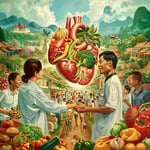

Undeterred, Mr. Somsak shared a comprehensive plan to tackle the threat head-on. This blueprint involves setting NCD prevention as a pivotal agenda item on the national stage, where synergy between various agencies will be key to controlling the rising tide of patients. A holistic approach is envisaged: reducing sodium intake, encouraging more exercise, bolstering protein consumption for stronger muscles, and fostering diets rich in good fats are just a few of the focal points.

To reinforce these efforts, the ministry intends to roll out dedicated NCD clinics across all hospitals, along with prevention centers reaching every district and community. This grassroots approach aims to make healthy living accessible to every Thai citizen, putting prevention firmly in the spotlight.

However, the elephant in the room was undeniably the relaxing of alcohol sales regulations. Critics were quick to point out the potential for this decision to undermine health objectives. But Mr. Somsak tackled this head-on, drawing a clear line between the two issues. He highlighted that the alcohol policy is primarily a maneuver designed to boost tourism. “The expansion of alcohol sales is about enhancing convenience for foreign tourists,” he explained, “It doesn’t necessarily mean that Thai people would consume more alcohol.”

For context, KrungSri Research provided insight into the drinking habits of the populace. Back in 2022, a total of 2.7 billion litres of alcohol flowed through the domestic market, with the average Thai person partaking in roughly seven litres each year. It’s a statistic that illuminates the cultural fabric of Thailand’s relationship with alcohol – a balancing act between tradition and modernity.

So, while the headlines may suggest a contradiction between health and leisure, the Ministry of Public Health maintains its stance: the strategies to cut down NCDs and the facilitation of alcohol sales are not parallel tracks set for collision. They are part of an intricate economic and social tapestry that demands both focus and flexibility.

Lifting the alcohol sales ban seems contradictory to their health goals. More alcohol access means more consumption, right?

Not necessarily, it’s really about boosting tourism and making it more convenient for them. Tourists don’t drink less just because of restricted hours.

I get that, but won’t this still encourage locals to drink more outside of those hours?

Let’s not underestimate the power of a campaign to improve public health. People can learn to make better choices alongside these changes.

This is just a ploy to get more tourist dollars. They don’t care about health.

It might bring in tourist dollars, but it’s also about balancing different aspects of society. Economics is part of health, too.

It’s always about money! I wish they focused more on the well-being of locals.

I think the approach of installing NCD clinics all over is the right direction. Prevention through education is key.

I’m all for letting people make their own choices. Educate them, then let them decide what they want to do.

Personal responsibility is important, but we must also consider societal influences. It’s not just about individual choices.

Agreed, Steve. Finding the balance is tricky though. Governments should educate more, I think.

7 litres per person per year doesn’t sound outrageous to me. How does this compare globally?

In some European countries, it’s much more. Thailand’s figure is relatively moderate.

This ban lift isn’t going to magically fix the tourism sector. There are deeper issues to address.

True, but it’s a start. Thailand needs to diversify tourism beyond just beaches and nightlife.

It’s good they are not compromising on health despite the alcohol policy. The intentions seem genuine to me.

Genuine intentions have to translate into effective actions. Words are just not enough.

Absolutely, Sue. Observing how this unfolds will be telling.

Why pretend it’s about public health when tourism dollars clearly drive this decision?

It’s strategic to maintain a balance. Economy impacts public health too—it funds hospitals and services.

It’s easy to forget that not all non-communicable diseases are related to alcohol, yet this is getting most attention.

Changing alcohol laws to align more with global standards can be positive in many ways.

I wonder if other countries will follow suit. We’ve seen similar discussions in Europe lately.

This conversation highlights the complexity of health policies. Nothing is as straightforward as it seems.

I’m a frequent visitor to Thailand. Ensuring I can enjoy a drink without timing issues is nice. Keeps up with the times!

I think they should focus on reducing sodium and increasing protein like they plan. It’s practical and achievable.

It’s a difficult balance for the government. I think their focus on NCD clubs in districts is a progressive step.

How will they ensure districts follow through with these health initiatives? Implementation can often be lacking.