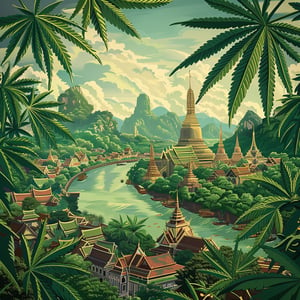

There’s a palpable buzz in Nakhon Phanom as Wat Phra That Phanom readies itself for a festival that blends devotion, pageantry and a touch of modern-day excitement. The annual ceremony at the province’s most venerated stupa begins on January 26 and runs through February 3 — nine days and nine nights of prayers, processions and traditions that draw pilgrims from both Thailand and neighboring Laos.

At the center of the pre-festival preparations was a solemn and beautifully staged ritual led by Police Colonel Doctor Manus Nonuch, chairman of the Miracle of Life Foundation, who performed a formal act of seeking forgiveness from Phra That Phanom ahead of the festivities. The ceremony felt both intimate and grand: traditional rites carried out with meticulous care, and an unmistakable sense that something special was about to unfold. Picture courtesy of KhaoSod.

Joining Manus were important religious and civic figures — Phra Khru Sri Phanom Khun, assistant abbot of Wat Phra That Phanom, and Jakarin Bowornchai, director of the One Heart for the People project. Together they presented an offering table that seemed lifted from a folk epic: atop it sat a seven-headed, seven-coloured Naga throne, surrounded by the kinds of traditional offerings that honor the stupa’s ancient guardians.

Brahmin Doctor Yutthapong Majwiset, a well-known ceremonial practitioner, presided over the ritual, calling on divine guardians and the protective Nagas of Phra That Phanom. After the reading of sacred scriptures, Manus and his team lit nine auspicious candles and laid out their offerings before the revered stupa, asking for blessings for the festival and for the safe arrival of pilgrims by both land and water.

The ritual wasn’t only solemn — it was also a feast for the eyes. Nineteen dancers performed a graceful tribute to the largest stupa in northeastern Thailand, their movements measured and reverent, adding a lyrical human note to the ceremony’s spiritual purpose. Many devotees took part in a heartfelt tradition: writing their names on yellow cloth prepared by the temple, then processing around the stupa three times before draping the cloth over the sacred structure. The procession felt like a communal promise, a wrapping of hopes and prayers around a monument that has stood for centuries.

Amid all this sacred choreography, one small, surprising detail set social media alight. During the ceremony a ceremonial incense stick revealed the number 536 — an unplanned flash of numerology that had onlookers smiling and whispering. Pictures and videos of the incense, shared widely, sparked a fevered rush for lottery tickets. Stalls outside the temple reported that combinations based on that mysterious sequence — 53, 35, 63, 36, 65 and 56 — flew off the shelves almost as quickly as they were printed.

Sudden lottery mania is now part of many Thai festivals, where sacred happenings and everyday superstition often meet. At Wat Phra That Phanom the two came together like old friends: a thousand-year-old stupa, a Brahmin’s invocations, and a modern crowd eager to translate auspicious signs into hope. Picture courtesy of KhaoSod.

The formal program for January 26 is as rich as the pre-festival ceremony. At 7:30 a.m., a religious procession will raise Phra Upakut from the Mekong River’s “navel” — a symbolic and dramatic act meant to invoke protection and sanctify the opening of the festival. Later, at 3:30 p.m., Mongkol Surasajja, the Senate chairman, will officially inaugurate the event, marking the start of nine days of ritual and celebration. Picture courtesy of KhaoSod.

What makes this festival enduringly powerful is its ability to gather people across borders and generations. Thai and Lao devotees come together not simply to witness spectacle, but to express gratitude, seek blessings and renew communal ties. For many pilgrims, the trip to Wat Phra That Phanom is as much a spiritual journey as it is a cultural reunion — the stupa becomes a focal point where private prayers and public tradition meet.

Outside the formal ceremonies there will be food stalls, local crafts, and the everyday hum of a community hosting a pilgrimage. Expect incense smoke to mingle with the aroma of grilled snacks, the bright colors of ceremonial cloths to flutter in the breeze, and the steady pulse of devotion underscoring every moment.

As the lanterns are lit and the processions wind their way around the stupa, Wat Phra That Phanom’s festival will be both a deeply rooted religious observance and a living, breathing celebration of local culture. Whether you come for the sacred rites, the dancers, the chance encounter with an auspicious number, or simply to soak up the atmosphere, the stupa’s doors are open: centuries of faith and tradition are ready to welcome the next wave of pilgrims.

For those planning to attend, remember to honor the rituals and the space — dress respectfully, join the communal offerings if you wish, and perhaps bring a little patience for the crowds and the unexpected little moments that make festivals like this unforgettable.

Picture courtesy of KhaoSod.

I grew up near Phra That Phanom and this article makes me proud and a little uneasy at the same time. The rituals and the Naga throne sound magnificent, but the sudden lottery frenzy every year feels like it cheapens the sacred moment. Still, I’ll be there on the first day to watch the procession and pray.

Turning a sacred incense flash into a lottery craze is exactly the problem with mixing faith and commerce. People should be focusing on the ritual’s meaning, not trying to monetize omens. This trend feels disrespectful to the elders who taught us reverence.

But isn’t the lottery part of local culture now? It doesn’t stop people from being reverent; they just have hope in a different form.

Local culture evolves, Joe. My worry is the temple’s aura becoming a tourist trap where peddlers profit off devotion.

Nita, I get what you’re saying — I felt the same when I saw the incense photos go viral. Yet sometimes those small superstitions give people comfort and a shared excitement.

The involvement of a Police Colonel leading a forgiveness ritual raises important questions about the blending of authority and religious symbolism. It’s fascinating from an anthropological perspective, but one must ask whether civic leaders are co-opting spiritual capital. The Brahmin ceremony layered on top further illustrates syncretic ritual dynamics in the region.

Anthropologically, this syncretism is common in Southeast Asia; power figures gain legitimacy via ritual participation. The question is who benefits materially from the heightened visibility.

Exactly — when politicians or police appear central, it can shift the festival from communal worship to a stage for political theater.

I appreciate the points. I’m not saying leaders shouldn’t participate, but transparency about their roles and ensuring no undue influence is crucial.

Food stalls and crafts are great, but I’ve watched prices spike during festivals as if pilgrims have wallets of gold. The commercialization takes the grassroots out of the pilgrimage. Someone should regulate the vendors to keep it fair.

Regulation risks killing the market though; part of the charm is bargaining with local sellers. Overregulation could harm local livelihoods.

There’s a balance: fair pricing and space for locals without letting outside vendors monopolize the good spots.

As a Lao devotee, I feel happy seeing us gather with Thai pilgrims. These rituals remind me of family reunions and shared faith. Cross-border gatherings keep our traditions alive despite political borders.

Numbers on incense sticks? That’s superstition at its finest. People will believe anything if it gives them hope. I just wish faith wasn’t so easily turned into gambling.

Please remember to dress respectfully if you attend; temples are not a fashion runway. Respect makes space better for everyone, pilgrims and locals alike.

Ha, 536 or bust! I might grab a ticket just for the story. Superstition aside, festivals are fun and full of energy.

The ritual of raising Phra Upakut from the Mekong has deep symbolic geography: invoking river spirits and territorial sanctity. The involvement of Senate-level officials is intriguing; it signals state endorsement of cultural heritage. This festival is a case study in how ritual, nationalism, and tourism intertwine.

As someone who has seen decades of these processions, the state’s presence has changed things but the people’s faith remains the anchor. Officials come and go, but the chants and offerings persist.

State endorsement can protect heritage, but it also risks commodifying it for political gain. The difference lies in intent and outcomes.

Agreed. We should study outcomes: does state involvement fund preservation or merely stage-manage culture for votes and photos?

I remember when the festival was quieter; now there are lights, lanterns, and big crowds from Laos and beyond. It feels crowded but also vibrant, like the whole community is awake. I pray they keep the ceremony’s heart intact.

Calling the Miracle of Life Foundation and a Police Colonel prominent in a ritual seems off to me; is this spiritual practice or PR? We must be critical when public servants front religious spectacles. Religion should not be a vehicle for image management.

Sometimes public figures help with logistics and safety, which can be positive. But transparency is key — are they offering service or seeking influence?

Ananda, I agree leaders sometimes help with traffic and security, which is practical. But when they take center stage in ceremonies it does feel like a PR move.

I like the dancers and the number 536 looks cool. My teacher says numbers can mean different things to different people. I want to see the lanterns.

The yellow cloth tradition is touching — wrapping the stupa with names feels like a collective hug. Those small acts keep ancient monuments connected to living people. I hope tourists respect the practice.

As a ceremonial practitioner I see how Brahmin rites and Buddhist traditions coexist respectfully here, creating layers of meaning rather than contradiction. Ritual efficacy often depends on communal belief and continuity of practice. We must protect those techniques and explain them to curious visitors.

Why do so many outsiders rush to buy lottery tickets instead of donating to the temple? It seems like a missed opportunity to support the place that holds these ceremonies. Maybe temples should offer a clear way to give during festivals.

There is beauty in syncretism, but also risk when rituals become spectacles for social media. Sacred moments distorted into viral content can lose depth. We should teach digital etiquette around holy sites.

The incense ‘number reveal’ might be a small coincidence blown up by cameras, but humans crave patterns and meaning. Whether you call it superstition or faith, the social cohesion from shared belief matters. Still, gambling harms for some families, so there’s a moral cost.

I’ve been going to Phra That Phanom for 40 years and every generation worries the festival will change. Yet it endures. Maybe change is the only way tradition survives in modern times.

This reads like a PR piece — lots of polish and very little on the problems pilgrims face like sanitation, safety, and vendor exploitation. Celebrate, yes, but don’t ignore the real-life issues that come with mass crowds.

If the community organized clean-up crews and price boards for vendors, it could be better for everyone. Festivals are opportunities for civic engagement, not just passive consumption.

I love the cross-border aspect but worry about how authorities handle Lao pilgrims’ documentation and access. Spiritual unity is wonderful but practical barriers still exist. Organizers should ensure equal treatment for all devotees.

mee, last year volunteers helped many Lao pilgrims with paperwork and translations, which made a big difference. Small community-led initiatives can solve real problems without waiting for officials.

Can we talk about safety around the Mekong procession? Raising Phra Upakut from the river sounds symbolic but could be hazardous with crowds and boats. Authorities should prioritize clear safety measures.

Rin makes a point: pageantry plus water is risky. Crowd control and trained volunteers are cheap insurance against tragedy, and organizers should be shamed if they ignore that.

Imagine the photos: incense numbers, dancers, the Mekong at sunrise. Viral content won’t hurt the tradition if it brings younger people back. I’m torn but leaning toward optimism.

User123, youth engagement is important, but viral moments shouldn’t override teaching respect. Festivals can be both contemporary and reverent if communities set boundaries.

I’ll end by saying: go with curiosity and humility. Bring offerings, not expectations, and if you buy a lottery ticket, remember the larger purpose of the festival.