In a case that reads like a cyber-thriller with a very real and heartbreaking ending, Thai and Chinese nationals accused of orchestrating a meticulously planned scam have been arrested after forcing a 19-year-old university student into a 24-hour video-call charade that culminated in him emptying his mother’s safe of nearly 10 million baht. The Technology Crime Suppression Division (TCSD) made the arrest public on November 23, with Police Lieutenant General Surapol Prembut briefing the media and instructing Police Major General Sarayut Chunnawat and Police Colonel Chakkrit Srirojankul to update on the probe.

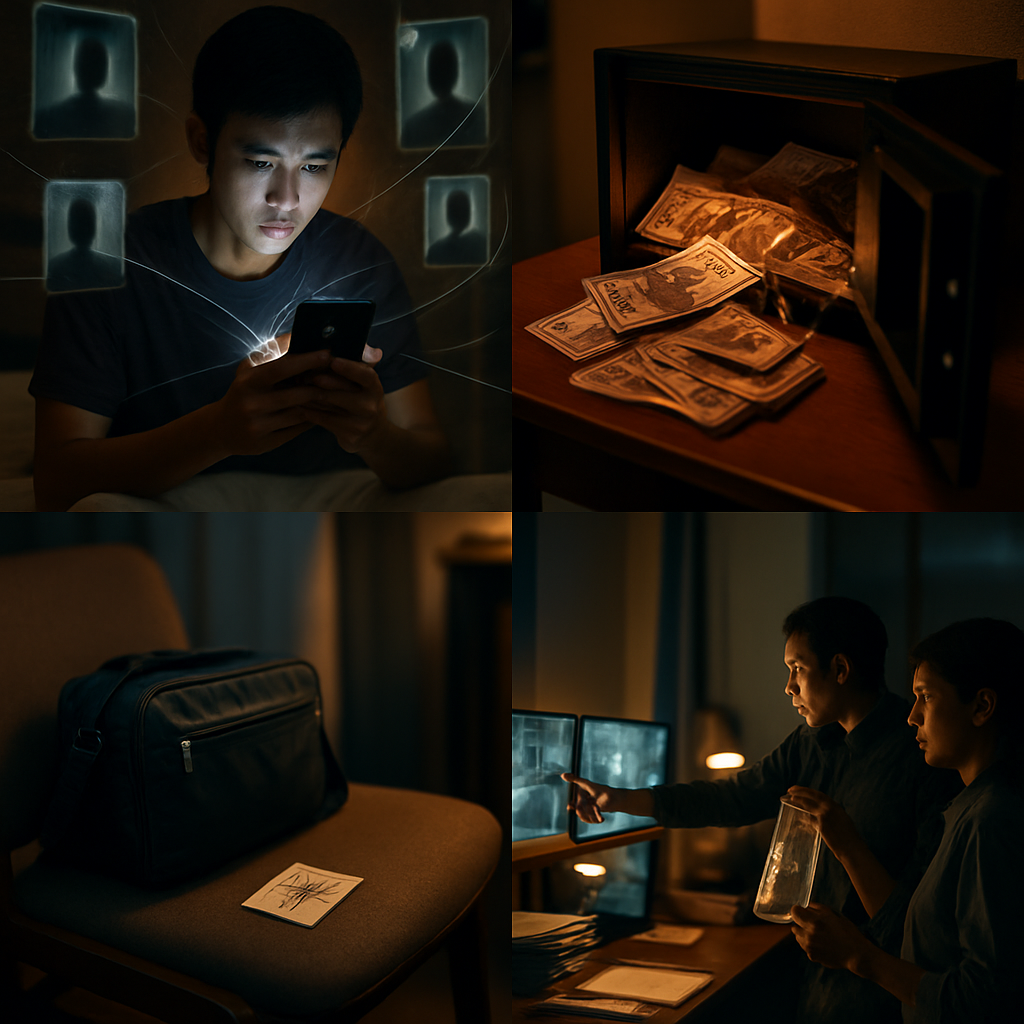

The victim, identified only as “Nick,” is a 19-year-old technical university student who became ensnared after what began as routine phone conversations with an unknown caller. The scammers cultivated his trust, asked him to add them on Line, and then bombarded him with counterfeit documents that looked disturbingly official — fake letters imitating the Anti‑Money Laundering Office, cyber police, and other government agencies. Isolated by his young age and introverted nature, Nick found it hard to spot the deception. When the fraudsters told him he was wanted by the court and needed to travel to Bueng Kan province to give testimony, fear for his mother’s legal safety pushed him to comply.

The timeline is chillingly methodical. On November 19, at noon, Nick was persuaded to skip classes and check into a hotel alone to avoid suspicion. The scam’s engine ran on continuous video calls designed to monitor and manipulate him. The perpetrators instructed him to return home and, while on camera, open and empty his mother’s safe so they could “verify” the valuables. By 6pm, he had transported the items from Samut Prakan province to Bang Phlap municipality in Nonthaburi province — all under the scammers’ watchful eye. That same night they soothed him, insisting he’d done the right thing and warning him not to tell anyone.

When the scheme didn’t end there, the deception morphed into further extraction. On the morning of November 20, the fraudsters pressured Nick into transferring additional funds, claiming the initial haul wasn’t sufficient for verification. Using his mother’s phone, he made several transactions totaling several hundred thousand baht across four transfers. The alarm was raised only when the mother noticed suspicious withdrawals and reported the activity to the Samut Prakan police station.

Investigators from the TCSD teamed up with cyber police to reconstruct the scam. CCTV footage and evidence from the Nonthaburi drop-off point pointed to an organized operation; a Chinese national allegedly tasked with collecting the valuables was detained and questioned. Authorities say the operation unfolded in clear phases — grooming, intimidation via fake government documentation, enforced livestream surveillance, and physical collection — and they are working to locate other accomplices and recover the stolen assets. Local media outlet KhaoSod has been following the case closely.

This isn’t an isolated headline — it’s part of a worrying trend. In a separate but related incident reported recently, a 22-year-old Thai university student in Udon Thani named Thongtae was left effectively homeless after unwittingly allowing a Vietnamese classmate to use his bank account as a mule. The student’s account was frozen, he couldn’t pay his dorm fees, and he ended up sleeping in a faculty common area while the investigation stagnated.

What makes these scams so effective is not advanced hacking but old-fashioned social engineering — a steady drip-feed of pressure, plausible-looking documents, and the careful exploitation of fear and loyalty. Scammers often impersonate official agencies on popular apps like Line, create a false sense of urgency, and then weaponize video calls to monitor victims in real time so victims can’t seek help or change their minds.

For anyone reading this, a few practical takeaways:

- Pause and verify. If someone claims to be from a government agency, hang up and call the official number listed on the agency’s website — don’t trust a number they give you.

- Never comply while under duress. Scammers rely on isolating victims and keeping them on a continuous call. Reach out to family or the authorities before you take action.

- Check bank activity frequently. Unusual transfers or sudden access issues should be reported immediately to your bank and local police.

- Keep devices secure. Don’t hand your phone or accounts over to someone else, and enable two-factor authentication where possible.

The TCSD’s announcement on November 23 underscores that the fight against these high‑tech confidence crimes is far from over. With suspects in custody and investigators combing CCTV and transaction trails, authorities say they will continue to pursue all leads and attempt to recover the assets. In a world where a friendly message on Line can spiral into a multimillion-baht loss, these cases are a sober reminder: vigilance is the best defense.

This is heartbreaking — how can anyone trick a kid into livestreaming his own theft? The scammers must be held fully accountable.

People keep saying “they were tricked” like that excuses lack of common sense; kids need better digital literacy, not pity.

Blaming the victim here is gross — he’s 19 and emotionally manipulated under duress, not a criminal mastermind who chose to rob his mother.

The social-engineering pattern here is textbook: grooming, official-looking docs, sustained video coercion. We should study the call logs and server metadata.

From a legal standpoint they could charge conspiracy, coercion, and organized fraud; cross-border cooperation will be crucial for evidence preservation.

Exactly — and digital forensics teams should prioritize timeline reconstruction from the victim’s device and the Line communications.

Line needs to be pressured to assist quickly; withholding or delaying metadata could hamper recovery efforts and prosecutions.

I feel so sorry for Nick and his mother. This shows how vulnerable introverted young people can be when targeted by fast, manipulative criminals.

Sympathy is fine but what about prevention? Schools should teach students how to verify government claims and use two-factor authentication.

Police are already pushing for public awareness campaigns; unfortunately we see repeat patterns and need better international legal tools.

Thanks for responding, Inspector — will the TCSD coordinate with the banks to freeze accounts faster when similar reports come in?

Beyond criminal charges, there are civil remedies and restraint orders useful in asset recovery; however, banking secrecy and cross-border transfers complicate restitution.

So the bank can undo stuff? That sounds complicated. I hope the family gets their money back.

It’s complicated but not impossible; immediate reporting, transaction tracing, and international mutual legal assistance can help recover assets if done quickly.

Scammers are everywhere now. I stopped using unknown links years ago and it saved me from trouble.

This makes me scared to answer calls from strangers. Why would someone look like police on Line? That’s fake, right?

Because scammers build fake authority. They act like officials to scare people; simple trick but very effective on the lonely or scared.

I will tell my friends to never give phones or do things while on a call with strangers.

We have detained several suspects and are pursuing others; the live-video coercion is a tactic we’ve warned about but it evolves every month.

Appreciate the update, Inspector — any guidance on what immediate steps victims should take to preserve evidence?

Keep the device as-is, do not delete messages, note times and account IDs, and report immediately to the nearest station and the bank.

Banks also need to improve real-time fraud detection; why did transfers go through without flagging massive withdrawals from an older account?

Banks have AML systems but they’re tuned for patterns, and determined fraudsters can game timing and thresholds; regulators must mandate faster response protocols.

Why is a Chinese national collecting the goods in Thailand allowed to operate — isn’t there more oversight at airports and borders now?

Cross-border actors exploit loopholes; enforcement at borders helps but digital identity verification and telecom cooperation are also key.

Makes sense. We need both offline and online checks to catch this.

A technical note: live video removes the victim’s ability to seek help and creates a false normalcy; apps should implement emergency break features that alert a pre-approved contact.

Good idea. An “I’m being coerced” quick-exit button could save lives if it silently notifies authorities or family.

Also, why are government agencies not batch-listing official contact numbers publicly in a way that’s easy to verify through messaging apps?

I smell negligence: apps, banks, and sometimes even police moving slowly while citizens lose everything — some of this is institutional failure.

Institutional failure or bureaucratic caution? Sometimes red tape exists for privacy, but it can feel like an excuse when victims lose millions.

This trend of using students’ accounts as mules is ugly — universities should offer emergency financial advice and temporary help for suspects until cases are resolved.

From a sociological perspective, these scams exploit trust networks — the perception of officialness and the appeal to filial obligation are exploited deliberately.

Why does the media always show the nationality of perpetrators? It feels like it stokes xenophobia instead of focusing on the criminal networks.

Reporting nationality can be relevant for cross-border investigations, but I agree it must be handled responsibly to avoid prejudice.

If the scammers used fake letters from the AML office, those agencies must issue public bulletins showing examples of forged documents so people can spot fakes.

I want to know if the mother will be charged for the transfers or if the police accept she was a victim too; families shouldn’t be penalized for being scammed.

This reads like a procedural failure across several systems: social safety nets, banking safeguards, and app moderation all fell short.

As a uni student, I worry — what if my account gets used? Universities should offer zero-tolerance support and legal advice for students trapped in scams.

Hard to be sympathetic to the scammers, but we must also avoid scaring young people into paranoia; teach verification without creating panic.

In my day con artists called you from a payphone; now it’s global and instantaneous, but the human psychology behind it is the same.

CCTV evidence is great, but without quick international arrests, recovery will be minimal. The window to trace assets is tiny.

Why is livestream coercion not treated as a distinct aggravating factor in sentencing? Being forced on camera adds trauma and control.

We should also critique how platforms verify government accounts; a blue check for officials would reduce impersonation on messaging apps.

The police need more resources — educating the public is fine, but when the crime industry is professionalized, enforcement must match that scale.

This will trend for a day and then disappear. I want long-term policy: mandatory fraud education in school curricula and app accountability.