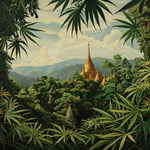

Picture this: Wat Pha Sukaram, a serene temple nestled in Chiang Rai’s Mae Sai, finds itself engulfed in floodwaters as early as September. Its abbot, in a plea for help, turns to the temple’s Facebook page, reaching out to the good Samaritans for aid, as people stranded in their homes nearby hope for a lifeline. This surreal scene, captured in a photo from the Wat Pha Sukaram Facebook page, tells only part of the story of Thailand’s recent battle with the elements.

This year, flooding has wreaked havoc across Thailand. In the devastating wake left behind, more than 50 souls in the north and at least 25 in the south have tragically lost their lives. Climate change plays a role, but it’s not the sole culprit. According to Pianporn “Pai” Deetes, the Southeast Asia programme director for the NGO International Rivers, several man-made issues are aggravating this crisis, which she shared in a candid discussion on the Bangkok Post’s “Deeper Dive” vodcast.

Deforestation, dams, and encroachment—these are the three primary culprits. Ironically, deforestation, a key trigger of flooding, is also responsible for the annual PM2.5 haze in northern Thailand. Forests are felled to plant corn for animal feed, and the aftermath of burning these cornfields brings about a local phenomenon described by Ms. Pianporn as “half flood, half haze.”

Mining, too, plays a notorious role, with satellite imagery revealing possible illegal mining activities in neighboring Myanmar’s Shan State. Following the coup three years ago, oversight dissolved, leaving a perilous vacuum. Without journalism or an active civil society, Myanmar reports fewer infractions, but activities like open-site mining and monocrop plantations are evident in the upper reaches of the Mae Sai River and Tachileik district, contributing to muddy floods sweeping through towns.

Deforestation compounds the flooding’s impact on populations, inundating cities and villages with mud and sediment. In Mae Sai, recovery lingers on, with heavy machines still toiling to excavate thick layers of sediment from people’s homes, as Ms. Pianporn outlined.

Adding to the watery woes are dams upstream, particularly those along the mighty Mekong. The deluge over the past months owes partly to these structures, with rainfall in China’s southern Yunnan compelling dam operators to unleash torrents downstream. “In Chiang Rai, floodwaters lingered,” noted Ms. Pianporn, “owing to the overwhelming volume coursing through the Mekong River.”

It’s critical for governments to engage in dialogue, especially when shared resources like international rivers are involved. Ms. Pianporn politely urged, “We are not pointing fingers, but it is crucial for China, being an upstream superpower, to heed the needs of its downstream neighbors as we share this lifeline.”

Encroachment on rivers rounds off the triumvirate of causes. An anecdote from a historian reveals that the true cause of floods in Chiang Rai City might lie beneath: old river courses upon which modern structures now stand. Even Ms. Pianporn’s maternal foundation office in the Chiang Rai outskirts is situated atop one such old waterway—a discovery that left her astounded.

Building flood walls, she asserts, is not the solution. These structures can become perilous if they fail, manifesting catastrophic consequences. Instead, Ms. Pianporn advocates for nature-based approaches, envisioning “sponge cities” that harmoniously integrate wetlands and lakes within urban landscapes. Relocating communities from vulnerable zones might become necessary, but such moves must occur inclusively and with fair compensation.

The pressing need, Ms. Pianporn emphasizes, is to collaborate with nature rather than resist it, and the cooperation of all stakeholders is paramount. “The key is recognizing the real problems, identifying crucial factors, and consulting with diverse parties—experts, engineers, farmers, urban residents, and academics,” she said. “The solution shouldn’t rest solely with the Royal Irrigation Department or Ministry of Interior. I believe together we can achieve it, but meaningful consultations with stakeholders are still missing.”

To explore these intricate dynamics further, click below to watch the full vodcast or search for ‘Deeper Dive Thailand’ wherever you find your podcasts. Let’s delve into this narrative that impacts us all, weaving together a tapestry of natural challenges and human resilience.

It’s frustrating seeing the same issues resurfacing every year. Maybe it’s time Thailand took serious action against deforestation and illegal mining?

True, but the economy heavily depends on these activities. Stopping them without a viable alternative could hurt more people.

But can you really put a price on lives and our environment? There’s a need for urgent balance and responsible actions.

Larissa, economic growth shouldn’t come at the expense of our planet. We must innovate towards sustainable practices!

Flooding and haze are not just environmental issues, they affect our health and lifestyle every single day. We can’t keep relying on temporary fixes.

Exactly, Anya! It’s baffling that nature-based solutions aren’t prioritized more. Sponge cities sound promising.

Sponge cities require significant planning and investment, not to mention a shift in mindset for many policymakers.

I agree, but isn’t any effort better than doing nothing? The long-term benefits could outweigh the costs.

Why not just build more dams to control the floods? Seems like a straightforward solution to me.

Dams can actually worsen situations by disrupting ecosystems and may cause more harm than good in the long run.

Plus, if those dams fail, you’re looking at catastrophic damage. Better to find a sustainable approach.

Can we really trust the government to handle this when they’ve failed so many times before? I think grassroots movements need to step up.

Grassroots are vital, but government policy is crucial for large-scale change. They both have roles to play.

I’m all for international cooperation, but do you really think China will listen about their dam policies? They’ve always prioritized their own interests.

What if we start by educating local communities about the impact they have? Change on a small scale can add up.

Education is key, but it needs to be paired with policy change and economic support for real impact.

It’s a shame things have come to this. Bet the government knew about the risks long before this became a crisis.

This isn’t just Thailand’s issue. Climate change is a global problem. International efforts would probably be more effective.

Absolutely. It’s a complex issue that requires coordinated action across borders.

Global tackling is needed, but it starts with localized solutions. Each country needs to do its part.

As a farmer, it’s tough seeing the backlash against agriculture. Sustainable practices are costly and not easy to implement without support.

That’s understandable, Grower134. Perhaps subsidies or government incentives could help shift practices sustainably.

Nature has shown us once too many times that it can’t be beaten – instead we should learn to live in harmony with it

That’s a hopeful view, Optimist69! But cooperation is key, not just harmony.

Agreed, Ava. It’s about finding and fostering balance.

Short-term action is needed but planning for the future is what will save lives. Why is that concept so hard for leaders to grasp?!

The mention of old river courses is fascinating. It’s ironic that modern cities might be suffering due to ancient landscapes.

Very true, HistoryBuff3. It makes you wonder how much historical knowledge we’re overlooking in today’s planning.