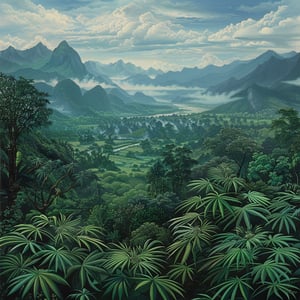

In the bustling Ministry of Labour premises in Tak, there’s quite the stir. It’s registration day for Myanmar workers awaiting their official permits, a doorway to working in Thailand. But underneath the regular procedure, ripples of change sweep through these hopeful migrants, hinged to a new directive from the home military government.

Sapphire-blue skies over Myanmar conceal an economy bearing the weight of uncertainty. The military government recently decreed that the nation’s expatriate workers should contribute at least a quarter of their overseas currency income to the local banking system, reshaping the landscape of foreign remittance.

As conveyed by esteemed Myanmar news outlet, The Irrawaddy, these foreign funds would undergo conversion to kyat, Myanmar’s official currency. The crux lies here – the conversion happens at the government’s official rate, which stands at an astounding 40% below the frequently-used market rate. Essentially, this strategy garners a lucrative pool of funds for government-related banking establishments, fortifying the junta’s precarious finances.

Given that there are approximately two million individuals of Myanmar origin legally employed in Thailand, this edict’s ramifications could prove consequential, rippling through not only the workers themselves but also their homebound families.

As per the new regulation since the first of September, prospective overseas workers must initiate a joint account at a bank operating under the Central Bank of Myanmar’s watchful eye. It is this account that renders itself a receptacle to 25% of their earnings.

Simultaneously, CB Bank, a significant private banking entity in Myanmar, directs its externally stationed migrant workers to channel a quarter of their salaries, whether monthly or once in three months, via sanctioned routes.

A discrepancy arises here – while the Thai currency witnesses junta-controlled exchange rates of merely 56 kyats per baht, the prevalent market rate circles closer to 100 kyats per baht, as per The Irrawaddy.

Under this system, a 20,000 baht monthly income would demand a 5,000 baht official remittance. Comparatively, unlicensed exchange operatives offer nearly 500,000 kyats for the identical amount.

The state also decreed that overseas residents dissenting from the imposed rule will face a three-year prohibition on off-shore work following the expiration of their current permit.

Government-appointed recruitment bodies have also received directions to modify agreements with migrant workers and shoulder the responsibility of transmitting 25% remittance through the Myanmar banking network.

On a slightly brighter note, the government offers certain inducements, such as tax-free property purchases and investment opportunities in Myanmar for income remittances via the official banking system or financial service providers licensed by the central bank.

Criticisms to these regulations were inevitable. One strong voice of objection belongs to Ko Nay Lin Thu, a Thailand-based advocate from the Aid Alliance Committee that assists migrant workers. He passionately condemned the government’s command – dubbing the exploitation of migrant workers as insupportable.

Be First to Comment