Amidst the sweltering chaos of Bangkok’s bustling streets, a seemingly innocuous scene unfolds at the Asok intersection: a cavalcade of vehicles grinding to a halt at the traffic light. It’s a familiar sight to those who navigate the urban jungle daily. The static cars reflect a collective patience thinned by a recurring bottleneck. But inside this picture, a much larger story brews—a brewing storm over the city’s approach to traffic management backed by the political engines of the People’s Party (PP).

In a move that has sparked intense public dialogue, the government has proposed implementing traffic congestion fees, aiming to unclog these notorious Bangkok streets. However, the PP, led by the outspoken Surachet Praweewongwut, staunchly opposes this measure. To them, it’s akin to applying a bandaid to an injury that requires surgery. Surachet argues vehemently for comprehensive improvements to the public transport network, advocating for a solution that genuinely addresses the root cause of the congestion afflicting the city.

According to Surachet, the idea of congestion charges drifts too far from practicality. Amidst the struggle to switch from private cars to public modes of transport, many commuters find themselves burdened under the weight of multiple costs. The high prices of electric train fares are compounded by the necessity of motorcycle taxis just to reach the stations—a fiscal labyrinth they’re forced to traverse daily. Not to mention the reliability, or rather the glaring lack of it, in the public bus services, which remain far from ideal.

The critique lays bare the fragmented nature of the transport ecosystem—a patchwork of uncoordinated services from electric trains to public buses, which operate in silos rather than in harmony. Surachet highlights a systemic inefficiency: “Subsidizing electric train fares benefits mainly the middle-income earners, leaving lower-income commuters reliant on an unreliable bus system,” he asserts. His plea is for a policy shift, one that addresses the imbalance and creates a genuinely appealing and viable alternative for all income brackets.

In what might seem a radical overhaul, Surachet pushes for a restructuring of fare systems. “Start fares at 8 baht and cap them at 45 baht, regardless of the mode,” he suggests, sketching a vision of an integrated fare model designed with commuter benefits at the heart, not as an afterthought. The examples he gives of pricing structures across different train lines serve as blueprints for a fairer system—one that eradicates the notion of inequality in the daily commute.

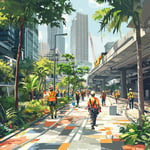

The PP’s strategy isn’t just about smarter fares; it’s about strategic integration. Surachet imagines a world where buses and trains work in seamless synergy, plugging gaps in service with pinpoint precision. It’s a call for the government to dig deeper, to truly assess the logistics of routes, and to organize transport modes in a symphony of efficiency and reliability, a much-needed orchestration to ease the city’s battered commuters.

Fellow PP MP, Suphanat Meenchainan, echoes these sentiments while drawing attention to another overlooked aspect: urban planning. He argues it plays a pivotal role—that the lack of effective planning exacerbates the congestion problem, compounding it into an ever-tightening noose around the city. Suphanat envisions mechanisms that spur operators to venture beyond the dense thicket of inner-city chaos, reducing the urban clutter that traps the capital in gridlock.

Suphanat poses a critical inquiry, turning the spotlight on governmental priorities: Is the government’s objective truly to ease congestion or merely to cut fares? He suggests that if it’s truly about traffic reduction, then the current strategies seem woefully inadequate. Instead of pouring funds into a fleeting solution, investing in genuinely expanding the transport network, particularly the bus systems, seems a more grounded approach.

It’s a timely discussion as Bangkok teeters on the precipice of growth and gridlock. As the city pulsates with life, the question remains—will the symphony of horns and engines continue to crescendo, or will a new tune play, orchestrating a future where urban travelers navigate with ease and grace instead of frustration and worry?

Implementing congestion fees is ridiculous! It’s just another way to tax people who already have to deal with high transport costs and unreliable services.

Exactly, and it doesn’t solve the root problem. We need better public transport first. Why not invest in reliable buses or lower train fares?

That’s my point! If public transport isn’t affordable or reliable, how can they expect people to switch from cars?

But isn’t a fee necessary to discourage unnecessary car use? Otherwise, it’ll never get better.

I disagree. A congestion fee might push the government and individuals to prioritize efficiency in public transportation.

Surachet Praweewongwut raises a valid point about fare restructuring. Making fares affordable and consistent would truly encourage the shift to public transport.

Affordability is key! But how do we ensure that low fares don’t translate to low quality services?

By holding operators accountable through consistent checks and subsidies that are smartly allocated.

Agreed. But is fare restructuring alone enough? We need transparency on where these funds go.

Why isn’t urban planning ever a priority? Suphanat is right, without solid planning, we will remain stuck in this loop of traffic hell.

Urban planning is essential, but it needs years. Immediate changes like enforcing congestion fees should happen now.

Immediate action is good, but not if it keeps patching ongoing problems. Real solutions need real work.

Maybe it’s a balance of both? Short-term fees while improving planning for the future.

Investments should focus on sustainable transport alternatives like cycling paths and clean energy trams. Time for innovation!

Innovative ideas are great, but we need foundational fixes first. Like AvocadoGreens mentioned, we need a complete overhaul.

I agree, change starts with a vision but needs a practical base.

With Surachet pushing this agenda, it’s obvious something positive will be done soon. He’s had notable success with reforms in the past.

While Surachet’s ideas sound promising, we need collective willpower to make drastic changes. Is Bangkok ready for this level of overhaul?

People need incentives to shift transportation modes. Congestion fees could be used to subsidize public transport directly.

Using fees to improve public transport could work, but only if there’s transparency and fairness in implementation.

That’s a good point, Haruto! Transparency ensures trust, which is necessary for long-term success.

I just hope Thailand looks at other global cities and learns. Look at Singapore or London, successful integration is possible!

The fragmented system is like a mismatched puzzle. Integrated systems must be a priority or else it’s all talk.

Public pressure can drive policymakers to actually address these issues. Keep your voices loud in support of these reforms!

It’s an endless loop of proposals and promises. Unless a strong political resolve backs it, good luck seeing any changes.

I like Surachet’s stance, but doesn’t charging more to drive unfairly target lower-income individuals who need their cars for work?

Exactly, and it widens the gap between those who can afford alternatives and those who can’t.

It feels like paying the government twice: first through taxes, then again with fees that are supposed to help us.

True, but if it funds a better system for the future, maybe it’s a sacrifice some people would have to make temporarily.

The congestion fees could just be a money grab unless someone watches over how funds are spent. Watchdog anyone?

Look, funds alone won’t solve it. They need to understand daily commuter challenges. Reality check, politicians!

So tired of every solution being either fee this or tax that. Where’s the creativity in political thinking?

Everyone needs flexibility in travel modes. Want to reduce cars? Make alternatives better, not punish car owners.

If everyone was forced to pay a fee, then could those funds go to forest conservation or green urban projects?