Located on the border between Thailand and Myanmar, the notorious KK Park has become a grim assembly point for the unfortunate victims of a vast network of scam centres. Trapped in this limbo, individuals who were duped or trafficked into working in these operations found themselves at ground zero during a sweeping multinational crackdown on criminal compounds run by gangs, with associations to the Karen Border Guard Force in Myawaddy, Myanmar.

These scam centres, long a fixture along the Thai-Myanmar corridor, have resurfaced into mainstream consciousness following the dramatic abduction and subsequent release of a famous Chinese actor in Thailand. This high-profile incident sparked an unprecedented alliance between Thailand, China, and Myanmar, all joining forces to dismantle the intricate webs spun by these centres, nestled among various Southeast Asian terrains.

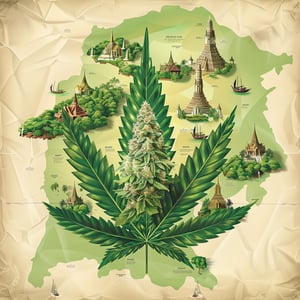

The breadth of deception these scams have perpetrated is staggering. According to the United Nations, criminal gangs have funneled hundreds of thousands into such centres, yielding illicit profits that soar into the billions annually. But what exactly are these scam centres? Predominantly based in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, these operations execute elaborate online scams to defraud unsuspecting individuals. The malicious masterminds behind these operations often reach out through social networks and messaging platforms, nurturing online relationships with their victims before persuading them to participate in fraudulent investments, notably schemes revolving around cryptocurrencies, ominously dubbed “pig butchering.” By exploiting these connections, scammers also engage in money laundering and illegal gambling, always seeking new avenues to exploit.

The focal point of the ongoing crackdown primarily rests in the Myawaddy region of Myanmar, straddling the Thai border, where scam centres enjoy the immunity granted by armed factions like the Karen National Army (KNA) and the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA). The seeds of these scams were first sown within the lightly regulated confines of casinos and online gambling dens, burgeoning in the 1990s, before sprawling into an industry by the 2000s, according to the United States Institute of Peace (USIP).

One notable epicentre is Shwe Kokko, a colossal scam compound established in 2017 by the esteemed Yatai International Holdings Group of Hong Kong, in concert with a precursor faction of the KNA, then under the Myanmar military’s aegis, masquerading as a sophisticated casino haven. Despite claims to the contrary, Yatai has been embroiled in accusations of criminality and human trafficking. The Covid-19 pandemic served as a catalyst for these operations, as stated by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Lockdowns and stringent border controls thwarted the usual gambling escapades, prompting criminal groups to innovate by converting facilities into cyber-scamming compounds.

These criminal networks are primarily composed of entities hailing from China, operating in coordination with armed groups in Myanmar’s Myawaddy region, as noted by USIP. Harrowing tales from those freed paint a bleak picture of coercion and torture rampant within these compounds. Jiang-aligned factions have also reputedly sustained these centres, causing consternation in Beijing as they were engulfed amidst the chaos of the “Operation 1027” offensive launched by anti-junta rebels in 2023.

A deep dive by Reuters in 2023 unearthed troubling links, tracing at least $9 million tied to “pig butchering” scams to an account commanded by a conspicuously well-connected figure from a Chinese trade association in Thailand.

Efforts to shatter these rings are escalating, with regional countries amplifying their onslaught against them. Thailand has cut electrical and fuel supplies, and severed internet connections to zones in Myanmar synonymous with scam activities. This crusade was ignited by the January abduction of Chinese actor Wang Xing in Thailand, which spiraled into a storm within Chinese social media circuits. Although swiftly rescued in Myawaddy and returned home, his ordeal raised alarm bells in Thailand, a nation heavily reliant on Chinese tourism revenue.

In the meantime, the Myanmar junta has detained over 3,700 foreign nationals implicated with these scam centres from January onwards, with upwards of 750 deported. As recently as last month, China orchestrated the return of approximately 200 citizens from Thailand’s Mae Sot district, abutting Myawaddy. The fallout from these raids has seen about 7,000 individuals, predominantly of Chinese descent, seeking refuge in camps directed by the KNA and DKBA.

The Thai efforts have also branched out to Cambodia, with authorities there achieving the liberation of more than 215 people trapped in a scam compound. This synchronized struggle marks a decisive chapter in the global battle against the pervasive menace of scam centres, underlining a collaborative resolve to combat this deeply entrenched criminal enterprise.

I think the crackdown on scam centres is long overdue. It’s crazy how these operations have been running for years!

Sure, it’s overdue, but let’s not forget the complicity of local authorities who turn a blind eye because of corruption.

Corruption is definitely a big issue. Wonder if it’s even possible to eradicate scams without tackling that first.

Exactly, and the sheer number of people affected makes me question how much further it has spread. Is it limited to Southeast Asia?

This whole thing with the actor abducted seems staged to me. What if it’s just a ploy to draw attention to the issue?

Really, Ana? You think they’d make up something like that? It sounds pretty genuine if you ask me.

Yes, Tim, I still think publicity stunts are common in global politics. It doesn’t mean the crackdown isn’t real though.

Staged or not, the end result is the same—an international focus on these scams. But Ana does make an interesting point about perception management.

Why do people keep falling for these online scams? Isn’t it obvious when something is too good to be true?

It’s easy to say that from the outside, but these scammers are really good at manipulation and targeting vulnerable people.

Education is key, but scammers are always one step ahead. By the time people catch on, they’ve evolved their tactics.

It’s a shame how the pandemic accelerated these crimes. You’d think people would come together to help, not exploit, in such times.

Unfortunately, Jacob, the pandemic made desperation and isolation worse, which is prime ground for scammers. It’s always about opportunity.

Do you think cutting electricity and fuel supplies is an effective way to combat these operations? It seems quite drastic.

It’s harsh, but when regular enforcement can’t reach these areas due to political tensions, it might be necessary.

Let’s hope these measures don’t catch innocent locals in the crossfire, though.

It’s terrifying to see the human trafficking element here. Slavery in modern times, who would’ve thought this still exists?

Right? And it’s not just in Asia, human trafficking is a global issue that needs a lot more attention.

Why isn’t the international community doing more to support these efforts? Seems like a drop in the ocean compared to the problem’s scope.

International politics, my friend. Everyone’s got their own agenda. It’s tough to make them care unless it affects them directly.

With 7,000 people seeking refuge, how are the camps dealing with potentially dangerous criminals among actual refugees?

Good point! Screening must be a nightmare, but separating criminals from victims is crucial.

Has technology really helped crack down on these operations, or does it just give scammers new tools to use against us?